The Mythical Monkey's essay about Buster Keaton and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle reads even better when one of the best silent movie DVD companies around cross-posts it.

Flicker Alley is currently promoting The Best Arbuckle/Keaton Collection, Vol. 1 &2 which will be available as a manufacture-on-demand DVD in March. As always, the Monkey encourages his readers to explore the wonderful world of silent movies. This would be a good place to start.

The Flicker Alley titles on my shelf, all of them definitive and essential:

Showing posts with label 1919. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1919. Show all posts

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Monday, February 9, 2015

The Buster Keaton Blogathon: The Roscoe Arbuckle Years, 1917-1920

I've been on the road for most of February and only this morning heard about the Buster Keaton Blogathon ongoing at Silent-ology. I cobbled together this contribution from some previous posts.

Of all the developments that made 1917 such a landmark year in film—the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist—perhaps the happiest for movie fans today was the big screen debut of the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

That Buster Keaton is only now arriving on the scene may come as a bit of a surprise to those of us who naturally think of Keaton as a contemporary of Chaplin—certainly we frame the debate "Chaplin versus Keaton" in those terms—but the fact is, Chaplin was already an international star with sixty films to his credit (including forty he directed himself) before Keaton ever set foot in a film studio. And although Keaton would brilliantly subvert most of the rules of early film comedy in a brief but prolific run between 1920 and 1928, it was by and large Chaplin who had established those rules, a fact that Keaton himself later conceded.

Which is not to say Keaton was an amateur when he joined Roscoe Arbuckle during the filming of The Butcher Boy in early 1917. He had been performing on the vaudeville stage with his parents from the age of four as part of a rough and tumble "knockabout" comedy act.

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."

Legend has it he was dubbed "Buster" when escape artist Harry Houdini saw the infant Keaton take a fall down a flight of stairs and bounce up unharmed. Whether he was born with it, or developed it doing routines with his father, if Keaton wasn't the most talented pratfall artist in movie history, I'd like to see the guy who survived long enough to be a better one. He did stunts that rivaled those of Douglas Fairbanks, and when he was done, he doubled for his co-stars and did their stunts, too.

"The secret," he once said, "is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat."

In early 1917, Keaton was booked into New York's Winter Garden for a series of shows when he bumped into Roscoe Arbuckle while strolling down Broadway.

For those of you who only know Arbuckle—"Fatty" to his fans, "Roscoe" to his friends—through the tabloid scandal and subsequent trial that (despite his acquittal) ended his career, you're missing out on one of the greatest comedic actor-directors of the silent era. Although I wouldn't put him in the same league as "the three geniuses"—Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd—Arbuckle was, in terms of his popularity and impact, the best of the rest, the very top of the second tier of comedians that included Mabel Normand, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, Ford Sterling and Max Linder.

Mark Bourne in his review of the Arbuckle/Keaton collection for The DVD Journal suggested that Arbuckle was to his biggest commercial rival, Charlie Chaplin, what Adam Sandler is these days to Woody Allen, "less artistic and sophisticated by miles, but nonetheless obviously skilled and unquestionably popular with his own characteristic wacky and raucous manner."

The collaboration between Keaton and Arbuckle was to prove pivotal for Buster.

"Arbuckle asked me if I'd ever been in a motion picture," Keaton told Kevin Brownlow in 1964. "I said I hadn't even been in a studio. He said, 'Come on down to the Norma Talmadge Studio on Forty-eighth Street on Monday. Get there early and do a scene with me and see how you like it.' Well, rehearsals [at the Winter Garden] hadn't started yet, so I said, 'all right.' I went down and we did it."

That first scene, in the Arbuckle short comedy The Butcher Boy, ends in one of the best of Keaton's early gags. At the 6:25 mark of the film, Keaton wanders into the country store where Arbuckle works as a butcher and by the end of the scene, Keaton's trademark porkpie hat is full of molasses and the store is a wreck.

"The first time I ever walked in front of a motion picture camera," he said, "that scene is in the finished motion picture and instead of doing just a bit [Arbuckle] carried me all the way through it."

It's a terrific sequence, but it's as notable for what isn't in it as what is—Keaton does not wear an outrageous costume or wild facial hair, nor does he indulge in the over-the-top reactions and shameless mugging common to the era. He's just a thoroughly average American—albeit, one who can take a swipe at Al St. John, do a 360º spin in mid-air and wind up flat on his back—who has somehow wandered in off the street and found himself thrust into the insanity of a two-reel silent comedy.

Keaton's understatement was the antithesis of the Mack Sennett approach, and was so wholly original, it constituted something of a revolution. Audiences and critics alike instantly took note, if not always approvingly.

"The deadpan was a natural," Keaton said. "As I grew up on the stage, experience taught me that I was the type of comedian that if I laughed at what I did, the audience didn't. Well, by the time I went into pictures when I was twenty-one, working with a straight face, a sober face, was mechanical with me.

"I got the reputation immediately [of being] called 'frozen face,' 'blank pan' and things like that. We went into the projection room and ran our first two pictures to see if I'd smiled. I hadn't paid any attention to it. We found out I hadn't. It was just a natural way of acting."

But deadpan, as any Keaton fan can tell you, isn't synonymous with inert, and as film historian Gilberto Perez has noted, Keaton was able to show us a face, "by subtle inflections, so vividly expressive of inner life. His large deep eyes are the most eloquent feature; with merely a stare he can convey a wide range of emotions, from longing to mistrust, from puzzlement to sorrow."

Keaton's next film with Arbuckle, The Rough House, is one of their best. Not only does it feature some of the best gags of Arbuckle's career—the dancing dinner rolls, trying to douse a raging fire with a teacup, squeezing out a bowl of soup with a sponge—but many film historians also now list Keaton as its uncredited co-director.

"The first thing I did in the studio," he told Robert and Joan Franklin in 1958, "was to tear that camera to pieces. I had to know how that film got into the cutting-room, what you did to it in there, how you projected it, how you finally got the picture together, and how you made things match. The technical part of pictures is what interested me."

Keaton and Arbuckle made three more comedies in 1917, His Wedding Night, Oh Doctor! and Coney Island. Each features an aspect of Keaton rarely seen after.

In the first, Keaton plays a milliner's delivery boy and winds up in drag as he models a wedding dress. Mistaking him for the bride, Al St. John kidnaps Keaton and hauls him off to the preacher at gunpoint.

In Oh, Doctor!, he plays Arbuckle's little boy, a reprise of the sort of comedy Keaton and his father Joe had done for years on stage, and pulls off a stunt you have to see to believe—Arbuckle smacks him, Keaton tumbles backwards over a table, picks up a book as he falls, and lands upright in a chair, with the book on his lap as if he's been there all along, reading comfortably.

And while Coney Island is mostly an excuse to watch Arbuckle caper around Luna Park—its plot of men wooing women on park benches is a throwback to the Keystone comedies—the film is worth seeking out for two reasons: one, for its documentary footage of Coney Island nearly one hundred years ago, and two, a rare chance to see Buster Keaton smile!

The smile notwithstanding, in terms of his look, his acting style, his fearless physical stunts and his fascination with technology, the basic Keaton was already on full display in these early two-reel comedies. He had only to add the context—that of a rational man enmeshed in the machinery of a universe that exists only to achieve absurd ends—for his unique brand of humor to reach its full flower.

In 1918, Keaton made five more two-reel comedies with Arbuckle before shipping off to France to serve in the army during World War I. Although not credited as such, by this time Keaton was working as the assistant director when Arbuckle, the credited director, was in front of the camera.

"You fell into those jobs," Keaton said later. "He never referred to me as the assistant director, but I was the guy who sat alongside of the camera and watched scenes that he was in. I ended up just practically co-directing with him."

The new balance in their collaboration showed up in front of the camera as well. In the first three films of 1918, he and Arbuckle are equal partners, more Laurel and Hardy—with Keaton as a thin straight man and Arbuckle a rotund goof—than the star/supporting player dynamic of 1917. The first film of the year, Out West is a parody of the Western genre, popular at the time, with Arbuckle playing a drifter riding the rails who winds up working for Keaton as an uncharacteristically tough saloon owner. Parody would soon prove to be one of Keaton's trademarks—indeed, his two-reeler The Frozen North in 1922 was such a savage parody of William S. Hart's "good bad guy" westerns that Hart refused to speak to Keaton for two years.

Next up was The Bell Boy, the story of two Stooge-like bellhops in a shabby hotel. The horse-drawn elevator is pure Keaton who was always fascinated by machines, and built several movies around them, culminating in his classic train picture, The General.

The film that followed, Moonshine, is the most Keatonesque of all his collaborations with Arbuckle. Ostensibly the story of a pair of inept revenuers (Keaton and Arbuckle) hot on the trail of West Virginia bootleggers, this is really a movie about movies, with the title cards constantly breaking the fourth wall to explain the filming process. "Look, this is only a two-reeler," one says, "We don't have time to build up to love scenes." Opening up the mechanics of movie making for laughs was a Keaton trick he would revisit time and again, culminating with Sherlock Jr. in 1924 when a projectionist gets sucked into the film itself.

The next two shorts, Good Night, Nurse and The Cook, both came out after Keaton had shipped out for the European war and his contributions look hasty, as if he filmed a couple of scenes for both, leaving the main plot for Arbuckle to flesh out later. Still, they're both worth a look, particularly The Cook which was thought to be lost for decades until rediscovered in Norway in 1999.

After a year in the Army left Keaton deaf in one ear, he went right back to making short films with Arbuckle. The first of them, Back Stage, is a traditional "hey kids, lets put on a play" story with one extraordinary scene—anticipating Keaton's most famous stunt in 1928's Steamboat Bill Jr., a house falls on Arbuckle only to miss him thanks to an open second floor window. Here, the house is only a cardboard stage prop and, unlike that latter example which might have killed Keaton, nobody is in danger, but seeing this early attempt at a famous gag is a bit like finding a preliminary sketch of Picasso's Guernica on the back of a cocktail napkin.

There were two more shorts, The Hayseed in 1919 and The Garage in 1920, after which Arbuckle left to make full-length feature films, but not before leaving the keys to the studio to Keaton. With Arbuckle's public blessing, Keaton began to direct films of his own.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Of all the developments that made 1917 such a landmark year in film—the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist—perhaps the happiest for movie fans today was the big screen debut of the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

That Buster Keaton is only now arriving on the scene may come as a bit of a surprise to those of us who naturally think of Keaton as a contemporary of Chaplin—certainly we frame the debate "Chaplin versus Keaton" in those terms—but the fact is, Chaplin was already an international star with sixty films to his credit (including forty he directed himself) before Keaton ever set foot in a film studio. And although Keaton would brilliantly subvert most of the rules of early film comedy in a brief but prolific run between 1920 and 1928, it was by and large Chaplin who had established those rules, a fact that Keaton himself later conceded.

Which is not to say Keaton was an amateur when he joined Roscoe Arbuckle during the filming of The Butcher Boy in early 1917. He had been performing on the vaudeville stage with his parents from the age of four as part of a rough and tumble "knockabout" comedy act.

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."

Legend has it he was dubbed "Buster" when escape artist Harry Houdini saw the infant Keaton take a fall down a flight of stairs and bounce up unharmed. Whether he was born with it, or developed it doing routines with his father, if Keaton wasn't the most talented pratfall artist in movie history, I'd like to see the guy who survived long enough to be a better one. He did stunts that rivaled those of Douglas Fairbanks, and when he was done, he doubled for his co-stars and did their stunts, too.

"The secret," he once said, "is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat."

In early 1917, Keaton was booked into New York's Winter Garden for a series of shows when he bumped into Roscoe Arbuckle while strolling down Broadway.

For those of you who only know Arbuckle—"Fatty" to his fans, "Roscoe" to his friends—through the tabloid scandal and subsequent trial that (despite his acquittal) ended his career, you're missing out on one of the greatest comedic actor-directors of the silent era. Although I wouldn't put him in the same league as "the three geniuses"—Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd—Arbuckle was, in terms of his popularity and impact, the best of the rest, the very top of the second tier of comedians that included Mabel Normand, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, Ford Sterling and Max Linder.

Mark Bourne in his review of the Arbuckle/Keaton collection for The DVD Journal suggested that Arbuckle was to his biggest commercial rival, Charlie Chaplin, what Adam Sandler is these days to Woody Allen, "less artistic and sophisticated by miles, but nonetheless obviously skilled and unquestionably popular with his own characteristic wacky and raucous manner."

The collaboration between Keaton and Arbuckle was to prove pivotal for Buster.

"Arbuckle asked me if I'd ever been in a motion picture," Keaton told Kevin Brownlow in 1964. "I said I hadn't even been in a studio. He said, 'Come on down to the Norma Talmadge Studio on Forty-eighth Street on Monday. Get there early and do a scene with me and see how you like it.' Well, rehearsals [at the Winter Garden] hadn't started yet, so I said, 'all right.' I went down and we did it."

That first scene, in the Arbuckle short comedy The Butcher Boy, ends in one of the best of Keaton's early gags. At the 6:25 mark of the film, Keaton wanders into the country store where Arbuckle works as a butcher and by the end of the scene, Keaton's trademark porkpie hat is full of molasses and the store is a wreck.

"The first time I ever walked in front of a motion picture camera," he said, "that scene is in the finished motion picture and instead of doing just a bit [Arbuckle] carried me all the way through it."

It's a terrific sequence, but it's as notable for what isn't in it as what is—Keaton does not wear an outrageous costume or wild facial hair, nor does he indulge in the over-the-top reactions and shameless mugging common to the era. He's just a thoroughly average American—albeit, one who can take a swipe at Al St. John, do a 360º spin in mid-air and wind up flat on his back—who has somehow wandered in off the street and found himself thrust into the insanity of a two-reel silent comedy.

Keaton's understatement was the antithesis of the Mack Sennett approach, and was so wholly original, it constituted something of a revolution. Audiences and critics alike instantly took note, if not always approvingly.

"The deadpan was a natural," Keaton said. "As I grew up on the stage, experience taught me that I was the type of comedian that if I laughed at what I did, the audience didn't. Well, by the time I went into pictures when I was twenty-one, working with a straight face, a sober face, was mechanical with me.

"I got the reputation immediately [of being] called 'frozen face,' 'blank pan' and things like that. We went into the projection room and ran our first two pictures to see if I'd smiled. I hadn't paid any attention to it. We found out I hadn't. It was just a natural way of acting."

But deadpan, as any Keaton fan can tell you, isn't synonymous with inert, and as film historian Gilberto Perez has noted, Keaton was able to show us a face, "by subtle inflections, so vividly expressive of inner life. His large deep eyes are the most eloquent feature; with merely a stare he can convey a wide range of emotions, from longing to mistrust, from puzzlement to sorrow."

Keaton's next film with Arbuckle, The Rough House, is one of their best. Not only does it feature some of the best gags of Arbuckle's career—the dancing dinner rolls, trying to douse a raging fire with a teacup, squeezing out a bowl of soup with a sponge—but many film historians also now list Keaton as its uncredited co-director.

"The first thing I did in the studio," he told Robert and Joan Franklin in 1958, "was to tear that camera to pieces. I had to know how that film got into the cutting-room, what you did to it in there, how you projected it, how you finally got the picture together, and how you made things match. The technical part of pictures is what interested me."

Keaton and Arbuckle made three more comedies in 1917, His Wedding Night, Oh Doctor! and Coney Island. Each features an aspect of Keaton rarely seen after.

In the first, Keaton plays a milliner's delivery boy and winds up in drag as he models a wedding dress. Mistaking him for the bride, Al St. John kidnaps Keaton and hauls him off to the preacher at gunpoint.

In Oh, Doctor!, he plays Arbuckle's little boy, a reprise of the sort of comedy Keaton and his father Joe had done for years on stage, and pulls off a stunt you have to see to believe—Arbuckle smacks him, Keaton tumbles backwards over a table, picks up a book as he falls, and lands upright in a chair, with the book on his lap as if he's been there all along, reading comfortably.

And while Coney Island is mostly an excuse to watch Arbuckle caper around Luna Park—its plot of men wooing women on park benches is a throwback to the Keystone comedies—the film is worth seeking out for two reasons: one, for its documentary footage of Coney Island nearly one hundred years ago, and two, a rare chance to see Buster Keaton smile!

The smile notwithstanding, in terms of his look, his acting style, his fearless physical stunts and his fascination with technology, the basic Keaton was already on full display in these early two-reel comedies. He had only to add the context—that of a rational man enmeshed in the machinery of a universe that exists only to achieve absurd ends—for his unique brand of humor to reach its full flower.

In 1918, Keaton made five more two-reel comedies with Arbuckle before shipping off to France to serve in the army during World War I. Although not credited as such, by this time Keaton was working as the assistant director when Arbuckle, the credited director, was in front of the camera.

"You fell into those jobs," Keaton said later. "He never referred to me as the assistant director, but I was the guy who sat alongside of the camera and watched scenes that he was in. I ended up just practically co-directing with him."

The new balance in their collaboration showed up in front of the camera as well. In the first three films of 1918, he and Arbuckle are equal partners, more Laurel and Hardy—with Keaton as a thin straight man and Arbuckle a rotund goof—than the star/supporting player dynamic of 1917. The first film of the year, Out West is a parody of the Western genre, popular at the time, with Arbuckle playing a drifter riding the rails who winds up working for Keaton as an uncharacteristically tough saloon owner. Parody would soon prove to be one of Keaton's trademarks—indeed, his two-reeler The Frozen North in 1922 was such a savage parody of William S. Hart's "good bad guy" westerns that Hart refused to speak to Keaton for two years.

Next up was The Bell Boy, the story of two Stooge-like bellhops in a shabby hotel. The horse-drawn elevator is pure Keaton who was always fascinated by machines, and built several movies around them, culminating in his classic train picture, The General.

The film that followed, Moonshine, is the most Keatonesque of all his collaborations with Arbuckle. Ostensibly the story of a pair of inept revenuers (Keaton and Arbuckle) hot on the trail of West Virginia bootleggers, this is really a movie about movies, with the title cards constantly breaking the fourth wall to explain the filming process. "Look, this is only a two-reeler," one says, "We don't have time to build up to love scenes." Opening up the mechanics of movie making for laughs was a Keaton trick he would revisit time and again, culminating with Sherlock Jr. in 1924 when a projectionist gets sucked into the film itself.

The next two shorts, Good Night, Nurse and The Cook, both came out after Keaton had shipped out for the European war and his contributions look hasty, as if he filmed a couple of scenes for both, leaving the main plot for Arbuckle to flesh out later. Still, they're both worth a look, particularly The Cook which was thought to be lost for decades until rediscovered in Norway in 1999.

After a year in the Army left Keaton deaf in one ear, he went right back to making short films with Arbuckle. The first of them, Back Stage, is a traditional "hey kids, lets put on a play" story with one extraordinary scene—anticipating Keaton's most famous stunt in 1928's Steamboat Bill Jr., a house falls on Arbuckle only to miss him thanks to an open second floor window. Here, the house is only a cardboard stage prop and, unlike that latter example which might have killed Keaton, nobody is in danger, but seeing this early attempt at a famous gag is a bit like finding a preliminary sketch of Picasso's Guernica on the back of a cocktail napkin.

There were two more shorts, The Hayseed in 1919 and The Garage in 1920, after which Arbuckle left to make full-length feature films, but not before leaving the keys to the studio to Keaton. With Arbuckle's public blessing, Keaton began to direct films of his own.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Friday, August 17, 2012

J'accuse! (1919)

This is my contribution to the Speechless Blogathon now underway at Eternity of Dreams.

A contemporary of D.W. Griffith and Louis Feuillade, Abel Gance directed over fifty movies in a career that stretched from the silent era to 1972, but his reputation as one of France's greatest directors is founded on three silent movies, the epic bio-pic Napoleon (1927), 1923's La Roue ("The Wheel"), and this one, J'accuse! from 1919.

A contemporary of D.W. Griffith and Louis Feuillade, Abel Gance directed over fifty movies in a career that stretched from the silent era to 1972, but his reputation as one of France's greatest directors is founded on three silent movies, the epic bio-pic Napoleon (1927), 1923's La Roue ("The Wheel"), and this one, J'accuse! from 1919.

Contrary to what you might expect if you know anything about French history, the novelist Émile Zola and/or the phrase "J'Accuse," this is not an early film version of the infamous Dreyfus Affair, in which a virulently anti-semitic French military court-martialed Alfred Dreyfus for selling secrets to the Germans without evidence of anything other than that he was Jewish (after Zola's essay "J'accuse!"—"I accuse!"—turned Dreyfus into a cause célèbre, an investigation revealed that another officer was guilty of the crime).

Contrary to what you might expect if you know anything about French history, the novelist Émile Zola and/or the phrase "J'Accuse," this is not an early film version of the infamous Dreyfus Affair, in which a virulently anti-semitic French military court-martialed Alfred Dreyfus for selling secrets to the Germans without evidence of anything other than that he was Jewish (after Zola's essay "J'accuse!"—"I accuse!"—turned Dreyfus into a cause célèbre, an investigation revealed that another officer was guilty of the crime).

Instead, Gance tells a fictional tale set during World War I, a conflict Gance served in, was wounded during and then returned to in order to film authentic combat scenes for the film. The story, such as it is, concerns itself with a poet who is in love with a girl who has been forced against her will into marriage to a wealthy brute. The husband (Séverin-Mars, who later managed to star in 1923's La Roue despite dying in 1921) is the kind of guy who leaves slaughtered deer carcasses bleeding on the dining room table while he beats his wife. The poet (Romuald Joubé) writes naive pastorales which he rapturously reads to his bedridden mother. And the girl (Maryse Dauvray, who looks like Florence Vidor but isn't) frets by the window.

Instead, Gance tells a fictional tale set during World War I, a conflict Gance served in, was wounded during and then returned to in order to film authentic combat scenes for the film. The story, such as it is, concerns itself with a poet who is in love with a girl who has been forced against her will into marriage to a wealthy brute. The husband (Séverin-Mars, who later managed to star in 1923's La Roue despite dying in 1921) is the kind of guy who leaves slaughtered deer carcasses bleeding on the dining room table while he beats his wife. The poet (Romuald Joubé) writes naive pastorales which he rapturously reads to his bedridden mother. And the girl (Maryse Dauvray, who looks like Florence Vidor but isn't) frets by the window.

Fortunately, war breaks out before the husband makes good an implied threat to kill his wife and the poet. Both men march off to war while the girl is sent to live in shame with her in-laws.

And then in a series of improbable twists, the girl is taken captive by the advancing German army while the poet winds up as a lieutenant in command of a front line unit that includes the husband. When both men perform absurdly fanciful acts of heroism, mutual suspicion and resentment turns to grudging respect and even abiding friendship.

And then in a series of improbable twists, the girl is taken captive by the advancing German army while the poet winds up as a lieutenant in command of a front line unit that includes the husband. When both men perform absurdly fanciful acts of heroism, mutual suspicion and resentment turns to grudging respect and even abiding friendship.

The rest of the movie's twists and turns I'll leave to you to discover except to say that I didn't really believe in any of them. Gance moves his characters around like chairs on an empty stage in service of a plot that strains credulity and a message that is so muddled I can only assume I know what it is.

This is typical of the three films for which Gance is best know. Any individual image or sequence in a Gance movie is as beautiful as any you've ever seen, and the rapid cutting he employs strongly influenced the Russians (such as Sergei Eisenstein) who were busy developing the montage as a means of quickly compressing events that occur over a period of time or in many places at once.

This is typical of the three films for which Gance is best know. Any individual image or sequence in a Gance movie is as beautiful as any you've ever seen, and the rapid cutting he employs strongly influenced the Russians (such as Sergei Eisenstein) who were busy developing the montage as a means of quickly compressing events that occur over a period of time or in many places at once.

The problem is, Gance gleefully piles up image on top of image until whatever point he was trying to make or mood he was trying to evoke is muddied at best. Gance is a jazz musician lost in a solo that goes on so long both you and he forget what he's trying to play.

Fernando F. Croce of Slant magazine calls Gance's work "[f]ertile to a fault" and accurately complains that "Gance's ... experimental joyousness clashes with the film's disenchanted mood." Michael S. Gant writing for DVD Reviews notes that "Perhaps Gance, who, as silent-film historian Kevin Brownlow has written, thought of cinema 'not as a single art, but as a pantheon of all the arts,' couldn't constrain his creative fervor to fashion a coherent message." Even David Camak Pratt, an unabashed fan of the film writing for PopMatters admits "J’Accuse is a messy picture. The title (translating to I Accuse!), the director, and much of what has been written about the film insist that it is a pacifist manifesto. As such, it fails."

Fernando F. Croce of Slant magazine calls Gance's work "[f]ertile to a fault" and accurately complains that "Gance's ... experimental joyousness clashes with the film's disenchanted mood." Michael S. Gant writing for DVD Reviews notes that "Perhaps Gance, who, as silent-film historian Kevin Brownlow has written, thought of cinema 'not as a single art, but as a pantheon of all the arts,' couldn't constrain his creative fervor to fashion a coherent message." Even David Camak Pratt, an unabashed fan of the film writing for PopMatters admits "J’Accuse is a messy picture. The title (translating to I Accuse!), the director, and much of what has been written about the film insist that it is a pacifist manifesto. As such, it fails."

It's like the first time I saw Napoleon, I marveled at the beauty and technical innovations (such as the use of a handheld camera) on display in a sequence where the little boy Napoleon takes charge of a snowball fight at school. And then the scene kept going and going, for eight-and-a-half minutes, and it began to dawn on me, "What the what?—Spielberg didn't take this long to show the invasion of Normandy!"

It's like the first time I saw Napoleon, I marveled at the beauty and technical innovations (such as the use of a handheld camera) on display in a sequence where the little boy Napoleon takes charge of a snowball fight at school. And then the scene kept going and going, for eight-and-a-half minutes, and it began to dawn on me, "What the what?—Spielberg didn't take this long to show the invasion of Normandy!"

A sense of proportion is also the hallmark of a great artist (said the man who once wrote a 12,000 word blog post about the Marx Brothers).

So J'accuse!—"I accuse"—who of what? Gance is a little unclear, pointing his finger at so many targets (French leaders, old men, unfaithful wives, the sun in the sky), and denouncing them for so many sins (war, rape, adultery, profiteering, but also of not proving worthy of the troops and their cause), that in the end I have to assume he's accusing his audience of that defect common to all human beings that makes unhappiness possible in a world of so much beauty. Which is a rather gross simplification of war's—any war's—causes, but then it's a rare artist who has ever analyzed his way to a deeply-felt response to the grim realities of war.

So J'accuse!—"I accuse"—who of what? Gance is a little unclear, pointing his finger at so many targets (French leaders, old men, unfaithful wives, the sun in the sky), and denouncing them for so many sins (war, rape, adultery, profiteering, but also of not proving worthy of the troops and their cause), that in the end I have to assume he's accusing his audience of that defect common to all human beings that makes unhappiness possible in a world of so much beauty. Which is a rather gross simplification of war's—any war's—causes, but then it's a rare artist who has ever analyzed his way to a deeply-felt response to the grim realities of war.

In that sense, J'accuse! reminded me of Thomas Ince's Civilization (1916), another ambitious film that tried and failed to explain war in cosmic terms. Not until directors narrowed their focus to real stories of the men who fought and died in the Great War did they produce such classics as The Big Parade and All Quiet on the Western Front, films that didn't need to gild the message that war is a barbarous pursuit.

As for Gance in general and J'accuse! specifically, revel in the beauty of any given moment, admire and respect his influence on the craft of filmmaking, but abandon all hope ye who enter here looking for a coherent narrative.

As for Gance in general and J'accuse! specifically, revel in the beauty of any given moment, admire and respect his influence on the craft of filmmaking, but abandon all hope ye who enter here looking for a coherent narrative.

Postscript To capture the authentic footage of combat that shows up in part three of J'accuse!, Gance traveled with the United States Army's 28th Infantry Division during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918.

A contemporary of D.W. Griffith and Louis Feuillade, Abel Gance directed over fifty movies in a career that stretched from the silent era to 1972, but his reputation as one of France's greatest directors is founded on three silent movies, the epic bio-pic Napoleon (1927), 1923's La Roue ("The Wheel"), and this one, J'accuse! from 1919.

A contemporary of D.W. Griffith and Louis Feuillade, Abel Gance directed over fifty movies in a career that stretched from the silent era to 1972, but his reputation as one of France's greatest directors is founded on three silent movies, the epic bio-pic Napoleon (1927), 1923's La Roue ("The Wheel"), and this one, J'accuse! from 1919. Contrary to what you might expect if you know anything about French history, the novelist Émile Zola and/or the phrase "J'Accuse," this is not an early film version of the infamous Dreyfus Affair, in which a virulently anti-semitic French military court-martialed Alfred Dreyfus for selling secrets to the Germans without evidence of anything other than that he was Jewish (after Zola's essay "J'accuse!"—"I accuse!"—turned Dreyfus into a cause célèbre, an investigation revealed that another officer was guilty of the crime).

Contrary to what you might expect if you know anything about French history, the novelist Émile Zola and/or the phrase "J'Accuse," this is not an early film version of the infamous Dreyfus Affair, in which a virulently anti-semitic French military court-martialed Alfred Dreyfus for selling secrets to the Germans without evidence of anything other than that he was Jewish (after Zola's essay "J'accuse!"—"I accuse!"—turned Dreyfus into a cause célèbre, an investigation revealed that another officer was guilty of the crime). Instead, Gance tells a fictional tale set during World War I, a conflict Gance served in, was wounded during and then returned to in order to film authentic combat scenes for the film. The story, such as it is, concerns itself with a poet who is in love with a girl who has been forced against her will into marriage to a wealthy brute. The husband (Séverin-Mars, who later managed to star in 1923's La Roue despite dying in 1921) is the kind of guy who leaves slaughtered deer carcasses bleeding on the dining room table while he beats his wife. The poet (Romuald Joubé) writes naive pastorales which he rapturously reads to his bedridden mother. And the girl (Maryse Dauvray, who looks like Florence Vidor but isn't) frets by the window.

Instead, Gance tells a fictional tale set during World War I, a conflict Gance served in, was wounded during and then returned to in order to film authentic combat scenes for the film. The story, such as it is, concerns itself with a poet who is in love with a girl who has been forced against her will into marriage to a wealthy brute. The husband (Séverin-Mars, who later managed to star in 1923's La Roue despite dying in 1921) is the kind of guy who leaves slaughtered deer carcasses bleeding on the dining room table while he beats his wife. The poet (Romuald Joubé) writes naive pastorales which he rapturously reads to his bedridden mother. And the girl (Maryse Dauvray, who looks like Florence Vidor but isn't) frets by the window.Fortunately, war breaks out before the husband makes good an implied threat to kill his wife and the poet. Both men march off to war while the girl is sent to live in shame with her in-laws.

And then in a series of improbable twists, the girl is taken captive by the advancing German army while the poet winds up as a lieutenant in command of a front line unit that includes the husband. When both men perform absurdly fanciful acts of heroism, mutual suspicion and resentment turns to grudging respect and even abiding friendship.

And then in a series of improbable twists, the girl is taken captive by the advancing German army while the poet winds up as a lieutenant in command of a front line unit that includes the husband. When both men perform absurdly fanciful acts of heroism, mutual suspicion and resentment turns to grudging respect and even abiding friendship.The rest of the movie's twists and turns I'll leave to you to discover except to say that I didn't really believe in any of them. Gance moves his characters around like chairs on an empty stage in service of a plot that strains credulity and a message that is so muddled I can only assume I know what it is.

This is typical of the three films for which Gance is best know. Any individual image or sequence in a Gance movie is as beautiful as any you've ever seen, and the rapid cutting he employs strongly influenced the Russians (such as Sergei Eisenstein) who were busy developing the montage as a means of quickly compressing events that occur over a period of time or in many places at once.

This is typical of the three films for which Gance is best know. Any individual image or sequence in a Gance movie is as beautiful as any you've ever seen, and the rapid cutting he employs strongly influenced the Russians (such as Sergei Eisenstein) who were busy developing the montage as a means of quickly compressing events that occur over a period of time or in many places at once.The problem is, Gance gleefully piles up image on top of image until whatever point he was trying to make or mood he was trying to evoke is muddied at best. Gance is a jazz musician lost in a solo that goes on so long both you and he forget what he's trying to play.

Fernando F. Croce of Slant magazine calls Gance's work "[f]ertile to a fault" and accurately complains that "Gance's ... experimental joyousness clashes with the film's disenchanted mood." Michael S. Gant writing for DVD Reviews notes that "Perhaps Gance, who, as silent-film historian Kevin Brownlow has written, thought of cinema 'not as a single art, but as a pantheon of all the arts,' couldn't constrain his creative fervor to fashion a coherent message." Even David Camak Pratt, an unabashed fan of the film writing for PopMatters admits "J’Accuse is a messy picture. The title (translating to I Accuse!), the director, and much of what has been written about the film insist that it is a pacifist manifesto. As such, it fails."

Fernando F. Croce of Slant magazine calls Gance's work "[f]ertile to a fault" and accurately complains that "Gance's ... experimental joyousness clashes with the film's disenchanted mood." Michael S. Gant writing for DVD Reviews notes that "Perhaps Gance, who, as silent-film historian Kevin Brownlow has written, thought of cinema 'not as a single art, but as a pantheon of all the arts,' couldn't constrain his creative fervor to fashion a coherent message." Even David Camak Pratt, an unabashed fan of the film writing for PopMatters admits "J’Accuse is a messy picture. The title (translating to I Accuse!), the director, and much of what has been written about the film insist that it is a pacifist manifesto. As such, it fails." It's like the first time I saw Napoleon, I marveled at the beauty and technical innovations (such as the use of a handheld camera) on display in a sequence where the little boy Napoleon takes charge of a snowball fight at school. And then the scene kept going and going, for eight-and-a-half minutes, and it began to dawn on me, "What the what?—Spielberg didn't take this long to show the invasion of Normandy!"

It's like the first time I saw Napoleon, I marveled at the beauty and technical innovations (such as the use of a handheld camera) on display in a sequence where the little boy Napoleon takes charge of a snowball fight at school. And then the scene kept going and going, for eight-and-a-half minutes, and it began to dawn on me, "What the what?—Spielberg didn't take this long to show the invasion of Normandy!"A sense of proportion is also the hallmark of a great artist (said the man who once wrote a 12,000 word blog post about the Marx Brothers).

So J'accuse!—"I accuse"—who of what? Gance is a little unclear, pointing his finger at so many targets (French leaders, old men, unfaithful wives, the sun in the sky), and denouncing them for so many sins (war, rape, adultery, profiteering, but also of not proving worthy of the troops and their cause), that in the end I have to assume he's accusing his audience of that defect common to all human beings that makes unhappiness possible in a world of so much beauty. Which is a rather gross simplification of war's—any war's—causes, but then it's a rare artist who has ever analyzed his way to a deeply-felt response to the grim realities of war.

So J'accuse!—"I accuse"—who of what? Gance is a little unclear, pointing his finger at so many targets (French leaders, old men, unfaithful wives, the sun in the sky), and denouncing them for so many sins (war, rape, adultery, profiteering, but also of not proving worthy of the troops and their cause), that in the end I have to assume he's accusing his audience of that defect common to all human beings that makes unhappiness possible in a world of so much beauty. Which is a rather gross simplification of war's—any war's—causes, but then it's a rare artist who has ever analyzed his way to a deeply-felt response to the grim realities of war.In that sense, J'accuse! reminded me of Thomas Ince's Civilization (1916), another ambitious film that tried and failed to explain war in cosmic terms. Not until directors narrowed their focus to real stories of the men who fought and died in the Great War did they produce such classics as The Big Parade and All Quiet on the Western Front, films that didn't need to gild the message that war is a barbarous pursuit.

As for Gance in general and J'accuse! specifically, revel in the beauty of any given moment, admire and respect his influence on the craft of filmmaking, but abandon all hope ye who enter here looking for a coherent narrative.

As for Gance in general and J'accuse! specifically, revel in the beauty of any given moment, admire and respect his influence on the craft of filmmaking, but abandon all hope ye who enter here looking for a coherent narrative.Postscript To capture the authentic footage of combat that shows up in part three of J'accuse!, Gance traveled with the United States Army's 28th Infantry Division during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Broken Blossoms (1919)

This is my contribution to the Summer Under The Stars Blogathon underway at Sittin' on a Backyard Fence. For those of you in the United States, you can see Broken Blossoms on Turner Classic Movies tomorrow morning, August 15, 2012, at 6 a.m. You can see two other Gish films mentioned in this post, Orphans of the Storm and Intolerance at 7:45 a.m. and 8 pm, respectively. A good day to set your DVRs. Or just skip work entirely.

I've written about silent film director D.W. Griffith many times, both to praise him and to bury him, but I've been steadfast in my insistence that, love him or hate him, he was the most influential director of the silent era. "[W]hereas other directors simply parroted the techniques that worked on stage," I have written, "and wound up with actors in togas milling around in front of painted backdrops, Griffith seemed to understand from the outset that film presented its own unique set of problems and opportunities. By composing his actors within the frame, by relying on revealing actions rather than words and, especially, by juxtaposing images and events through editing, Griffith was able to create within his audience an emotional involvement in his stories."

I've written about silent film director D.W. Griffith many times, both to praise him and to bury him, but I've been steadfast in my insistence that, love him or hate him, he was the most influential director of the silent era. "[W]hereas other directors simply parroted the techniques that worked on stage," I have written, "and wound up with actors in togas milling around in front of painted backdrops, Griffith seemed to understand from the outset that film presented its own unique set of problems and opportunities. By composing his actors within the frame, by relying on revealing actions rather than words and, especially, by juxtaposing images and events through editing, Griffith was able to create within his audience an emotional involvement in his stories."

In effect, Griffith invented a film "language" and in the process created what we today think of as the modern movie, a contribution to film history as important as the invention of the camera itself.

If you're only going to see one D.W. Griffith movie in your life, Broken Blossoms starring Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess and Donald Crisp is the one to see. The Birth of a Nation is more (in)famous, Intolerance was more ambitious, and the nearly 500 shorts he made for Biograph between 1908 and 1913 were more influential. But in terms of a film that is moving, well-acted and accessible, that features all of Griffith's strengths without also suffering from his weaknesses, and let's be honest, that clocks in at a reasonable 88 minutes instead of 3-plus hours, Broken Blossoms is the only choice.

If you're only going to see one D.W. Griffith movie in your life, Broken Blossoms starring Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess and Donald Crisp is the one to see. The Birth of a Nation is more (in)famous, Intolerance was more ambitious, and the nearly 500 shorts he made for Biograph between 1908 and 1913 were more influential. But in terms of a film that is moving, well-acted and accessible, that features all of Griffith's strengths without also suffering from his weaknesses, and let's be honest, that clocks in at a reasonable 88 minutes instead of 3-plus hours, Broken Blossoms is the only choice.

Not only was Broken Blossoms the best picture of 1919, it was arguably the best silent movie made in film's first three decades.

If you're familiar with Griffith's work, you know he often painted on large canvases, tackling entire historical eras on sets the size of small cities. But if Intolerance was Griffith's Sistine Chapel, Broken Blossoms is as small and intimate as a portrait by Vermeer.

Based on Limehouse Nights, a collection of short stories by Thomas Burke set in the slums of London, Broken Blossoms is the story of Cheng Huan, a Chinese immigrant with naive dreams of teaching Buddha's philosophy of peace to those "sons of turmoil and strife," the barbarous Anglo-Saxons of England. "It is a tale of temple bells," says the opening title card, "sounding at sunset before the image of Buddha; it is a tale of love and lovers; it is a tale of tears."

Based on Limehouse Nights, a collection of short stories by Thomas Burke set in the slums of London, Broken Blossoms is the story of Cheng Huan, a Chinese immigrant with naive dreams of teaching Buddha's philosophy of peace to those "sons of turmoil and strife," the barbarous Anglo-Saxons of England. "It is a tale of temple bells," says the opening title card, "sounding at sunset before the image of Buddha; it is a tale of love and lovers; it is a tale of tears."

If you've never seen a silent movie, particularly one from film's earliest days, Griffith's skill at introducing Cheng to his audience might escape your attention. Griffith's legacy is so ubiquitous, we don't even notice it anymore, but if you've ever seen a movie or a television show, you've seen Griffith's style. First he establishes the mise-en-scène—an establishing shot of a Chinese treaty port, cutting to a closer shot of a particular part of town, then even closer to a single street, followed by near documentary shots of people on the street—a traveling shot of three girls, shots of a father with his children, including an over-the-shoulder shot of their reaction to his kindness, then a cut to "sky-larking American sailors."

The entire sequence takes a little more than ninety seconds, but with no more than the corner of a small set, and by my count some twenty extras, Griffith created the sense of a bustling foreign port town, both culturally diverse and completely alien to an American audience in 1919. Is it an important sequence? Only in the sense that it grounds the narrative in a reality that establishes the world Cheng moves in before we've even met him, a technique Griffith had invented while at Biograph and perfected in such films as The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.

The entire sequence takes a little more than ninety seconds, but with no more than the corner of a small set, and by my count some twenty extras, Griffith created the sense of a bustling foreign port town, both culturally diverse and completely alien to an American audience in 1919. Is it an important sequence? Only in the sense that it grounds the narrative in a reality that establishes the world Cheng moves in before we've even met him, a technique Griffith had invented while at Biograph and perfected in such films as The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.

Now go and look at the beginning of a movie as great as, say, Casablanca, or a television show as mundane as C.S.I., and see what I mean about how Griffith's approach to storytelling is ubiquitous.

Cheng is played by Richard Barthelmess, who was in the process of replacing Robert Harron as Griffith's go-to actor (just as Harron had replaced Henry Walthall). It may be a bit jarring for a modern audience to see Barthelmess, a white actor, in Asian makeup (actually just a rubber band around his forehead stretching his features tight across his skull) and perhaps it's a pity that Griffith didn't cast Sessue Hayakawa in the role, but I'll say two things in Griffith's defense and let it drop: 1) it was common practice in Hollywood for Caucasian actors, from Warner Oland to Paul Muni to (God help us) Mickey Rooney, to play Asians well into the 1960s, and 2) Richard Barthelmess gives the best performance of his career in this movie.

Cheng is played by Richard Barthelmess, who was in the process of replacing Robert Harron as Griffith's go-to actor (just as Harron had replaced Henry Walthall). It may be a bit jarring for a modern audience to see Barthelmess, a white actor, in Asian makeup (actually just a rubber band around his forehead stretching his features tight across his skull) and perhaps it's a pity that Griffith didn't cast Sessue Hayakawa in the role, but I'll say two things in Griffith's defense and let it drop: 1) it was common practice in Hollywood for Caucasian actors, from Warner Oland to Paul Muni to (God help us) Mickey Rooney, to play Asians well into the 1960s, and 2) Richard Barthelmess gives the best performance of his career in this movie.

Equally jarring, the film refers to Cheng as "the Yellow Man" throughout. But before your head explodes, let me point out that the term "Yellow Man" is used here both purposefully and ironically. As the film was being filmed, the United States was once again experiencing one of its periodic bouts of anti-immigrant xenophobia, this time directed at Asian-Americans, which the Hearst newspaper chain had dubbed "the Yellow Peril" and "the Yellow Terror." That Cheng, a modern-day Good Samaritan, turns out to be the film's most sympathetic and heroic character is a direct challenge to the prejudices of Griffith's audience. By using the racist term "Yellow Man" here, Griffith has set up his audience to do an about-face by the picture's end. Whether the device works or not, or is justified, is up to you, but be aware that it is a conscious artist choice.

Equally jarring, the film refers to Cheng as "the Yellow Man" throughout. But before your head explodes, let me point out that the term "Yellow Man" is used here both purposefully and ironically. As the film was being filmed, the United States was once again experiencing one of its periodic bouts of anti-immigrant xenophobia, this time directed at Asian-Americans, which the Hearst newspaper chain had dubbed "the Yellow Peril" and "the Yellow Terror." That Cheng, a modern-day Good Samaritan, turns out to be the film's most sympathetic and heroic character is a direct challenge to the prejudices of Griffith's audience. By using the racist term "Yellow Man" here, Griffith has set up his audience to do an about-face by the picture's end. Whether the device works or not, or is justified, is up to you, but be aware that it is a conscious artist choice.

Gish said later of Griffith, "He inspired in us his belief that we were working in a medium that was powerful enough to influence the whole world."

Cheng's mission to convert the heathen white man is preternaturally gentle, hopelessly naive, or both, and with a fade and an intertitle, Griffith leaps forward several years to the Limehouse District of London where Cheng is known only as a "Chink storekeeper." He's thinner, his back bent, his step slower, old now if not in years, then in spirit. The shot of Barthelemess standing against a wall with his head bowed, leg bent and arms wrapped around himself tells you everything you need to know about the intervening years—indeed, not only tells you what you need to know, but makes you feel it as well.

It's a masterful shot that eliminates the need for a half-hour's worth of exposition, and when in subsequent posts I complain of Abel Gance's and Erich von Stroheim's inability to get to the point by showing a single telling detail, this is the sort of simple sequence to which I'm referring.

It's a masterful shot that eliminates the need for a half-hour's worth of exposition, and when in subsequent posts I complain of Abel Gance's and Erich von Stroheim's inability to get to the point by showing a single telling detail, this is the sort of simple sequence to which I'm referring.

Having established Cheng, Griffith then introduces us to Battling Burrows and his daughter Lucy, played by, respectively, future Oscar-winner Donald Crisp and Griffith's favorite actress, Lillian Gish. Burrows is a prizefighter, a drunk, a preening ape with a cauliflower ear, and a father so cruel to his illegitimate daughter that the critic for Variety threw up at a private preview of the film.

Having established Cheng, Griffith then introduces us to Battling Burrows and his daughter Lucy, played by, respectively, future Oscar-winner Donald Crisp and Griffith's favorite actress, Lillian Gish. Burrows is a prizefighter, a drunk, a preening ape with a cauliflower ear, and a father so cruel to his illegitimate daughter that the critic for Variety threw up at a private preview of the film.

Nobody in Hollywood history has ever been better at playing pain and suffering than Gish, and here at last is a role that cuts right to the chase with no pretensions that she represented the flower of Victorian womanhood. No plucky Mary Pickford lass is she. Gish is a whipped dog, the very pantomime of defeat, working as a virtual slave to an abusive drunk who threatens her with the lash if she doesn't keep up a happy front, leading to perhaps the defining shot of Gish's great career—using her fingers to push the corners of her mouth into a grotesque, desperate approximation of a smile.

A later scene where Burrows breaks down the door of a closet where Gish's Lucy is hiding was so harrowing that during its filming one passerby called in the police. "My God," Griffith told Gish afterwards, "why didn't you warn me you were going to do that."

A later scene where Burrows breaks down the door of a closet where Gish's Lucy is hiding was so harrowing that during its filming one passerby called in the police. "My God," Griffith told Gish afterwards, "why didn't you warn me you were going to do that."

"The case could be made," wrote Matthew Kennedy for Bright Lights Film Journal, "for Gish's character as the most pitiable creature the movies have ever seen." According to Felicia Feaster writing for TCM, "one critic of the day cheekily proposed a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Lillian Gish."

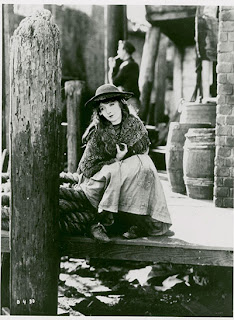

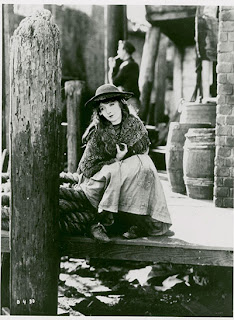

The scene where she sits on a dock by the river, her knee bent, her shawl pulled around her narrow shoulders, echoes the one of Barthelemess resting against a wall, again not only short-circuiting the need for more exposition, but also linking the two characters in the viewer's mind before they have even met.

The scene where she sits on a dock by the river, her knee bent, her shawl pulled around her narrow shoulders, echoes the one of Barthelemess resting against a wall, again not only short-circuiting the need for more exposition, but also linking the two characters in the viewer's mind before they have even met.

And meet they finally do. After Burrows beats her nearly to death, she stumbles through the streets of Limehouse until she reaches Cheng's doorstep. When he helps her, it is perhaps the first hint of kindness she's ever experienced—and responds with a genuine smile that touches Cheng's lonely heart. But a victim to the end, Lucy's hard-earned fear of men and her deeply-ingrained racism prevent her from fully embracing her salvation.

Those used to the epic scale and complex editing strategies of Griffith's best-known works will no doubt be surprised by the simplicity and delicacy of this chaste, tragic romance. The entire film takes place on a handful of modest sets with three main characters and as many supporting ones, yet the effect is deeper and more satisfying, at least to me, than anything else Griffith ever attempted. It's a virtuoso effort all the way around, with career turns by Barthelmess, Gish and Crisp, and the confident direction of a consummate artist.

Griffith directed Broken Blossoms for Adolph Zukor at Paramount Pictures, but Zukor— who made a similar mistake with Mary Pickford—was appalled at what he saw and refused to release it. The story goes that an enraged Griffith returned the next day with $250,000 in cash and bought the film back on the spot. Thus, it became the first release through the newly-formed United Artists and fortunately for Griffith, it was both a critical and commercial success.

Griffith directed Broken Blossoms for Adolph Zukor at Paramount Pictures, but Zukor— who made a similar mistake with Mary Pickford—was appalled at what he saw and refused to release it. The story goes that an enraged Griffith returned the next day with $250,000 in cash and bought the film back on the spot. Thus, it became the first release through the newly-formed United Artists and fortunately for Griffith, it was both a critical and commercial success.

Of the four main participants in Broken Blossoms, Lillian Gish went on the greatest success. After stellar performances in Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm, she left Griffith's employ, eventually landing at MGM where she signed a contract to make six pictures at $400,000 a year and with complete control over choice of cast, director and screenplay. While there, she made some of her best pictures, La Boheme, The Scarlet Letter and The Wind.

Of the four main participants in Broken Blossoms, Lillian Gish went on the greatest success. After stellar performances in Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm, she left Griffith's employ, eventually landing at MGM where she signed a contract to make six pictures at $400,000 a year and with complete control over choice of cast, director and screenplay. While there, she made some of her best pictures, La Boheme, The Scarlet Letter and The Wind.

After the advent of sound pictures, Gish turned to radio and the stage, but eventually returned to Hollywood, earning an Oscar nomination for her supporting role in Duel in the Sun (1946). These days she may be best known as the shotgun-toting granny in the noir classic The Night of the Hunter. She received an honorary Oscar in 1971 "[f]or superlative artistry and for distinguished contribution to the progress of motion pictures." She died in 1993 at the age of 99.

Donald Crisp went on to success not only as an actor but as a director as well, including co-directing the classic Buster Keaton comedy, The Navigator (in fact, his scenes in Broken Blossoms were filmed at night because he was directing a film of his own during the day). He worked steadily until his retirement in 1963, appearing in such films as Mutiny on the Bounty, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Sea Hawk, National Velvet and Pollyanna. In 1942, he won the Oscar for his supporting performance in How Green Was My Valley.

Donald Crisp went on to success not only as an actor but as a director as well, including co-directing the classic Buster Keaton comedy, The Navigator (in fact, his scenes in Broken Blossoms were filmed at night because he was directing a film of his own during the day). He worked steadily until his retirement in 1963, appearing in such films as Mutiny on the Bounty, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Sea Hawk, National Velvet and Pollyanna. In 1942, he won the Oscar for his supporting performance in How Green Was My Valley.

Richard Barthelmess proved to be one of the most popular actors during the silent era and for anyone looking to see him at his best, look not only at Broken Blossoms, but also at such films as Way Down East (1920) and The Enchanted Cottage (1924). In 1921, Barthelmess formed his own production company where he made one of his best received and remembered films, Tol'able David. Later he became one of the 36 founding members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and was nominated for the first Oscar for best actor (losing to Emil Jannings). His career went into a gradual decline during the sound era—maybe his best known sound role was as a pilot married to Rita Hayworth in Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings—but he continued to work until 1942 when he joined the Navy Reserve. After the war, he lived comfortably on his real estate investments and died in 1963.

Richard Barthelmess proved to be one of the most popular actors during the silent era and for anyone looking to see him at his best, look not only at Broken Blossoms, but also at such films as Way Down East (1920) and The Enchanted Cottage (1924). In 1921, Barthelmess formed his own production company where he made one of his best received and remembered films, Tol'able David. Later he became one of the 36 founding members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and was nominated for the first Oscar for best actor (losing to Emil Jannings). His career went into a gradual decline during the sound era—maybe his best known sound role was as a pilot married to Rita Hayworth in Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings—but he continued to work until 1942 when he joined the Navy Reserve. After the war, he lived comfortably on his real estate investments and died in 1963.

As for Griffith, I'm of the opinion that Broken Blossoms was his last completely-unqualified masterpiece. The bucolic fantasies and Victorian morality plays that would follow were wildly out-of-step with the tastes of audiences recently bathed in the blood of the Great War. The best of his remaining films, Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm, feature terrific performances (and in the case of the former, a concluding action sequence where Richard Barthelmess races across a disintegrating ice floe to rescue Lillian Gish just before she plunges over a waterfall—real ice, real waterfall, and two stars who were nearly killed), but the one is marred by heaps of cornpone humor, while the other, an epic retelling of the French Revolution, features some history lessons that, frankly, border on the ludicrous, even by Griffith's outlandish standards.

"Griffith in 1919," wrote Roger Ebert in his Great Movie series, "was the unchallenged king of serious American movies (only C.B. DeMille rivaled him in fame), and Broken Blossoms was seen as brave and controversial. What remains today is the artistry of the production, the ethereal quality of Lillian Gish, the broad appeal of the melodrama ... [a]nd its social impact. Films like this, naive as they seem today, helped nudge a xenophobic nation toward racial tolerance."

"Griffith in 1919," wrote Roger Ebert in his Great Movie series, "was the unchallenged king of serious American movies (only C.B. DeMille rivaled him in fame), and Broken Blossoms was seen as brave and controversial. What remains today is the artistry of the production, the ethereal quality of Lillian Gish, the broad appeal of the melodrama ... [a]nd its social impact. Films like this, naive as they seem today, helped nudge a xenophobic nation toward racial tolerance."

I've written about silent film director D.W. Griffith many times, both to praise him and to bury him, but I've been steadfast in my insistence that, love him or hate him, he was the most influential director of the silent era. "[W]hereas other directors simply parroted the techniques that worked on stage," I have written, "and wound up with actors in togas milling around in front of painted backdrops, Griffith seemed to understand from the outset that film presented its own unique set of problems and opportunities. By composing his actors within the frame, by relying on revealing actions rather than words and, especially, by juxtaposing images and events through editing, Griffith was able to create within his audience an emotional involvement in his stories."

I've written about silent film director D.W. Griffith many times, both to praise him and to bury him, but I've been steadfast in my insistence that, love him or hate him, he was the most influential director of the silent era. "[W]hereas other directors simply parroted the techniques that worked on stage," I have written, "and wound up with actors in togas milling around in front of painted backdrops, Griffith seemed to understand from the outset that film presented its own unique set of problems and opportunities. By composing his actors within the frame, by relying on revealing actions rather than words and, especially, by juxtaposing images and events through editing, Griffith was able to create within his audience an emotional involvement in his stories."In effect, Griffith invented a film "language" and in the process created what we today think of as the modern movie, a contribution to film history as important as the invention of the camera itself.

If you're only going to see one D.W. Griffith movie in your life, Broken Blossoms starring Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess and Donald Crisp is the one to see. The Birth of a Nation is more (in)famous, Intolerance was more ambitious, and the nearly 500 shorts he made for Biograph between 1908 and 1913 were more influential. But in terms of a film that is moving, well-acted and accessible, that features all of Griffith's strengths without also suffering from his weaknesses, and let's be honest, that clocks in at a reasonable 88 minutes instead of 3-plus hours, Broken Blossoms is the only choice.

If you're only going to see one D.W. Griffith movie in your life, Broken Blossoms starring Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess and Donald Crisp is the one to see. The Birth of a Nation is more (in)famous, Intolerance was more ambitious, and the nearly 500 shorts he made for Biograph between 1908 and 1913 were more influential. But in terms of a film that is moving, well-acted and accessible, that features all of Griffith's strengths without also suffering from his weaknesses, and let's be honest, that clocks in at a reasonable 88 minutes instead of 3-plus hours, Broken Blossoms is the only choice.Not only was Broken Blossoms the best picture of 1919, it was arguably the best silent movie made in film's first three decades.

If you're familiar with Griffith's work, you know he often painted on large canvases, tackling entire historical eras on sets the size of small cities. But if Intolerance was Griffith's Sistine Chapel, Broken Blossoms is as small and intimate as a portrait by Vermeer.

Based on Limehouse Nights, a collection of short stories by Thomas Burke set in the slums of London, Broken Blossoms is the story of Cheng Huan, a Chinese immigrant with naive dreams of teaching Buddha's philosophy of peace to those "sons of turmoil and strife," the barbarous Anglo-Saxons of England. "It is a tale of temple bells," says the opening title card, "sounding at sunset before the image of Buddha; it is a tale of love and lovers; it is a tale of tears."

Based on Limehouse Nights, a collection of short stories by Thomas Burke set in the slums of London, Broken Blossoms is the story of Cheng Huan, a Chinese immigrant with naive dreams of teaching Buddha's philosophy of peace to those "sons of turmoil and strife," the barbarous Anglo-Saxons of England. "It is a tale of temple bells," says the opening title card, "sounding at sunset before the image of Buddha; it is a tale of love and lovers; it is a tale of tears."If you've never seen a silent movie, particularly one from film's earliest days, Griffith's skill at introducing Cheng to his audience might escape your attention. Griffith's legacy is so ubiquitous, we don't even notice it anymore, but if you've ever seen a movie or a television show, you've seen Griffith's style. First he establishes the mise-en-scène—an establishing shot of a Chinese treaty port, cutting to a closer shot of a particular part of town, then even closer to a single street, followed by near documentary shots of people on the street—a traveling shot of three girls, shots of a father with his children, including an over-the-shoulder shot of their reaction to his kindness, then a cut to "sky-larking American sailors."

The entire sequence takes a little more than ninety seconds, but with no more than the corner of a small set, and by my count some twenty extras, Griffith created the sense of a bustling foreign port town, both culturally diverse and completely alien to an American audience in 1919. Is it an important sequence? Only in the sense that it grounds the narrative in a reality that establishes the world Cheng moves in before we've even met him, a technique Griffith had invented while at Biograph and perfected in such films as The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.

The entire sequence takes a little more than ninety seconds, but with no more than the corner of a small set, and by my count some twenty extras, Griffith created the sense of a bustling foreign port town, both culturally diverse and completely alien to an American audience in 1919. Is it an important sequence? Only in the sense that it grounds the narrative in a reality that establishes the world Cheng moves in before we've even met him, a technique Griffith had invented while at Biograph and perfected in such films as The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.Now go and look at the beginning of a movie as great as, say, Casablanca, or a television show as mundane as C.S.I., and see what I mean about how Griffith's approach to storytelling is ubiquitous.

Cheng is played by Richard Barthelmess, who was in the process of replacing Robert Harron as Griffith's go-to actor (just as Harron had replaced Henry Walthall). It may be a bit jarring for a modern audience to see Barthelmess, a white actor, in Asian makeup (actually just a rubber band around his forehead stretching his features tight across his skull) and perhaps it's a pity that Griffith didn't cast Sessue Hayakawa in the role, but I'll say two things in Griffith's defense and let it drop: 1) it was common practice in Hollywood for Caucasian actors, from Warner Oland to Paul Muni to (God help us) Mickey Rooney, to play Asians well into the 1960s, and 2) Richard Barthelmess gives the best performance of his career in this movie.

Cheng is played by Richard Barthelmess, who was in the process of replacing Robert Harron as Griffith's go-to actor (just as Harron had replaced Henry Walthall). It may be a bit jarring for a modern audience to see Barthelmess, a white actor, in Asian makeup (actually just a rubber band around his forehead stretching his features tight across his skull) and perhaps it's a pity that Griffith didn't cast Sessue Hayakawa in the role, but I'll say two things in Griffith's defense and let it drop: 1) it was common practice in Hollywood for Caucasian actors, from Warner Oland to Paul Muni to (God help us) Mickey Rooney, to play Asians well into the 1960s, and 2) Richard Barthelmess gives the best performance of his career in this movie. Equally jarring, the film refers to Cheng as "the Yellow Man" throughout. But before your head explodes, let me point out that the term "Yellow Man" is used here both purposefully and ironically. As the film was being filmed, the United States was once again experiencing one of its periodic bouts of anti-immigrant xenophobia, this time directed at Asian-Americans, which the Hearst newspaper chain had dubbed "the Yellow Peril" and "the Yellow Terror." That Cheng, a modern-day Good Samaritan, turns out to be the film's most sympathetic and heroic character is a direct challenge to the prejudices of Griffith's audience. By using the racist term "Yellow Man" here, Griffith has set up his audience to do an about-face by the picture's end. Whether the device works or not, or is justified, is up to you, but be aware that it is a conscious artist choice.

Equally jarring, the film refers to Cheng as "the Yellow Man" throughout. But before your head explodes, let me point out that the term "Yellow Man" is used here both purposefully and ironically. As the film was being filmed, the United States was once again experiencing one of its periodic bouts of anti-immigrant xenophobia, this time directed at Asian-Americans, which the Hearst newspaper chain had dubbed "the Yellow Peril" and "the Yellow Terror." That Cheng, a modern-day Good Samaritan, turns out to be the film's most sympathetic and heroic character is a direct challenge to the prejudices of Griffith's audience. By using the racist term "Yellow Man" here, Griffith has set up his audience to do an about-face by the picture's end. Whether the device works or not, or is justified, is up to you, but be aware that it is a conscious artist choice.Gish said later of Griffith, "He inspired in us his belief that we were working in a medium that was powerful enough to influence the whole world."

Cheng's mission to convert the heathen white man is preternaturally gentle, hopelessly naive, or both, and with a fade and an intertitle, Griffith leaps forward several years to the Limehouse District of London where Cheng is known only as a "Chink storekeeper." He's thinner, his back bent, his step slower, old now if not in years, then in spirit. The shot of Barthelemess standing against a wall with his head bowed, leg bent and arms wrapped around himself tells you everything you need to know about the intervening years—indeed, not only tells you what you need to know, but makes you feel it as well.

It's a masterful shot that eliminates the need for a half-hour's worth of exposition, and when in subsequent posts I complain of Abel Gance's and Erich von Stroheim's inability to get to the point by showing a single telling detail, this is the sort of simple sequence to which I'm referring.

It's a masterful shot that eliminates the need for a half-hour's worth of exposition, and when in subsequent posts I complain of Abel Gance's and Erich von Stroheim's inability to get to the point by showing a single telling detail, this is the sort of simple sequence to which I'm referring. Having established Cheng, Griffith then introduces us to Battling Burrows and his daughter Lucy, played by, respectively, future Oscar-winner Donald Crisp and Griffith's favorite actress, Lillian Gish. Burrows is a prizefighter, a drunk, a preening ape with a cauliflower ear, and a father so cruel to his illegitimate daughter that the critic for Variety threw up at a private preview of the film.