The Mythical Monkey's essay about Buster Keaton and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle reads even better when one of the best silent movie DVD companies around cross-posts it.

Flicker Alley is currently promoting The Best Arbuckle/Keaton Collection, Vol. 1 &2 which will be available as a manufacture-on-demand DVD in March. As always, the Monkey encourages his readers to explore the wonderful world of silent movies. This would be a good place to start.

The Flicker Alley titles on my shelf, all of them definitive and essential:

Showing posts with label 1917. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1917. Show all posts

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Monday, February 9, 2015

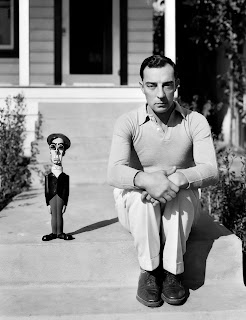

The Buster Keaton Blogathon: The Roscoe Arbuckle Years, 1917-1920

I've been on the road for most of February and only this morning heard about the Buster Keaton Blogathon ongoing at Silent-ology. I cobbled together this contribution from some previous posts.

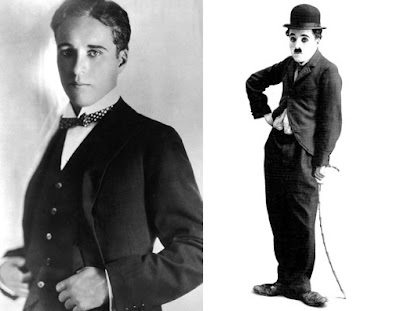

Of all the developments that made 1917 such a landmark year in film—the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist—perhaps the happiest for movie fans today was the big screen debut of the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

That Buster Keaton is only now arriving on the scene may come as a bit of a surprise to those of us who naturally think of Keaton as a contemporary of Chaplin—certainly we frame the debate "Chaplin versus Keaton" in those terms—but the fact is, Chaplin was already an international star with sixty films to his credit (including forty he directed himself) before Keaton ever set foot in a film studio. And although Keaton would brilliantly subvert most of the rules of early film comedy in a brief but prolific run between 1920 and 1928, it was by and large Chaplin who had established those rules, a fact that Keaton himself later conceded.

Which is not to say Keaton was an amateur when he joined Roscoe Arbuckle during the filming of The Butcher Boy in early 1917. He had been performing on the vaudeville stage with his parents from the age of four as part of a rough and tumble "knockabout" comedy act.

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."

Legend has it he was dubbed "Buster" when escape artist Harry Houdini saw the infant Keaton take a fall down a flight of stairs and bounce up unharmed. Whether he was born with it, or developed it doing routines with his father, if Keaton wasn't the most talented pratfall artist in movie history, I'd like to see the guy who survived long enough to be a better one. He did stunts that rivaled those of Douglas Fairbanks, and when he was done, he doubled for his co-stars and did their stunts, too.

"The secret," he once said, "is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat."

In early 1917, Keaton was booked into New York's Winter Garden for a series of shows when he bumped into Roscoe Arbuckle while strolling down Broadway.

For those of you who only know Arbuckle—"Fatty" to his fans, "Roscoe" to his friends—through the tabloid scandal and subsequent trial that (despite his acquittal) ended his career, you're missing out on one of the greatest comedic actor-directors of the silent era. Although I wouldn't put him in the same league as "the three geniuses"—Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd—Arbuckle was, in terms of his popularity and impact, the best of the rest, the very top of the second tier of comedians that included Mabel Normand, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, Ford Sterling and Max Linder.

Mark Bourne in his review of the Arbuckle/Keaton collection for The DVD Journal suggested that Arbuckle was to his biggest commercial rival, Charlie Chaplin, what Adam Sandler is these days to Woody Allen, "less artistic and sophisticated by miles, but nonetheless obviously skilled and unquestionably popular with his own characteristic wacky and raucous manner."

The collaboration between Keaton and Arbuckle was to prove pivotal for Buster.

"Arbuckle asked me if I'd ever been in a motion picture," Keaton told Kevin Brownlow in 1964. "I said I hadn't even been in a studio. He said, 'Come on down to the Norma Talmadge Studio on Forty-eighth Street on Monday. Get there early and do a scene with me and see how you like it.' Well, rehearsals [at the Winter Garden] hadn't started yet, so I said, 'all right.' I went down and we did it."

That first scene, in the Arbuckle short comedy The Butcher Boy, ends in one of the best of Keaton's early gags. At the 6:25 mark of the film, Keaton wanders into the country store where Arbuckle works as a butcher and by the end of the scene, Keaton's trademark porkpie hat is full of molasses and the store is a wreck.

"The first time I ever walked in front of a motion picture camera," he said, "that scene is in the finished motion picture and instead of doing just a bit [Arbuckle] carried me all the way through it."

It's a terrific sequence, but it's as notable for what isn't in it as what is—Keaton does not wear an outrageous costume or wild facial hair, nor does he indulge in the over-the-top reactions and shameless mugging common to the era. He's just a thoroughly average American—albeit, one who can take a swipe at Al St. John, do a 360º spin in mid-air and wind up flat on his back—who has somehow wandered in off the street and found himself thrust into the insanity of a two-reel silent comedy.

Keaton's understatement was the antithesis of the Mack Sennett approach, and was so wholly original, it constituted something of a revolution. Audiences and critics alike instantly took note, if not always approvingly.

"The deadpan was a natural," Keaton said. "As I grew up on the stage, experience taught me that I was the type of comedian that if I laughed at what I did, the audience didn't. Well, by the time I went into pictures when I was twenty-one, working with a straight face, a sober face, was mechanical with me.

"I got the reputation immediately [of being] called 'frozen face,' 'blank pan' and things like that. We went into the projection room and ran our first two pictures to see if I'd smiled. I hadn't paid any attention to it. We found out I hadn't. It was just a natural way of acting."

But deadpan, as any Keaton fan can tell you, isn't synonymous with inert, and as film historian Gilberto Perez has noted, Keaton was able to show us a face, "by subtle inflections, so vividly expressive of inner life. His large deep eyes are the most eloquent feature; with merely a stare he can convey a wide range of emotions, from longing to mistrust, from puzzlement to sorrow."

Keaton's next film with Arbuckle, The Rough House, is one of their best. Not only does it feature some of the best gags of Arbuckle's career—the dancing dinner rolls, trying to douse a raging fire with a teacup, squeezing out a bowl of soup with a sponge—but many film historians also now list Keaton as its uncredited co-director.

"The first thing I did in the studio," he told Robert and Joan Franklin in 1958, "was to tear that camera to pieces. I had to know how that film got into the cutting-room, what you did to it in there, how you projected it, how you finally got the picture together, and how you made things match. The technical part of pictures is what interested me."

Keaton and Arbuckle made three more comedies in 1917, His Wedding Night, Oh Doctor! and Coney Island. Each features an aspect of Keaton rarely seen after.

In the first, Keaton plays a milliner's delivery boy and winds up in drag as he models a wedding dress. Mistaking him for the bride, Al St. John kidnaps Keaton and hauls him off to the preacher at gunpoint.

In Oh, Doctor!, he plays Arbuckle's little boy, a reprise of the sort of comedy Keaton and his father Joe had done for years on stage, and pulls off a stunt you have to see to believe—Arbuckle smacks him, Keaton tumbles backwards over a table, picks up a book as he falls, and lands upright in a chair, with the book on his lap as if he's been there all along, reading comfortably.

And while Coney Island is mostly an excuse to watch Arbuckle caper around Luna Park—its plot of men wooing women on park benches is a throwback to the Keystone comedies—the film is worth seeking out for two reasons: one, for its documentary footage of Coney Island nearly one hundred years ago, and two, a rare chance to see Buster Keaton smile!

The smile notwithstanding, in terms of his look, his acting style, his fearless physical stunts and his fascination with technology, the basic Keaton was already on full display in these early two-reel comedies. He had only to add the context—that of a rational man enmeshed in the machinery of a universe that exists only to achieve absurd ends—for his unique brand of humor to reach its full flower.

In 1918, Keaton made five more two-reel comedies with Arbuckle before shipping off to France to serve in the army during World War I. Although not credited as such, by this time Keaton was working as the assistant director when Arbuckle, the credited director, was in front of the camera.

"You fell into those jobs," Keaton said later. "He never referred to me as the assistant director, but I was the guy who sat alongside of the camera and watched scenes that he was in. I ended up just practically co-directing with him."

The new balance in their collaboration showed up in front of the camera as well. In the first three films of 1918, he and Arbuckle are equal partners, more Laurel and Hardy—with Keaton as a thin straight man and Arbuckle a rotund goof—than the star/supporting player dynamic of 1917. The first film of the year, Out West is a parody of the Western genre, popular at the time, with Arbuckle playing a drifter riding the rails who winds up working for Keaton as an uncharacteristically tough saloon owner. Parody would soon prove to be one of Keaton's trademarks—indeed, his two-reeler The Frozen North in 1922 was such a savage parody of William S. Hart's "good bad guy" westerns that Hart refused to speak to Keaton for two years.

Next up was The Bell Boy, the story of two Stooge-like bellhops in a shabby hotel. The horse-drawn elevator is pure Keaton who was always fascinated by machines, and built several movies around them, culminating in his classic train picture, The General.

The film that followed, Moonshine, is the most Keatonesque of all his collaborations with Arbuckle. Ostensibly the story of a pair of inept revenuers (Keaton and Arbuckle) hot on the trail of West Virginia bootleggers, this is really a movie about movies, with the title cards constantly breaking the fourth wall to explain the filming process. "Look, this is only a two-reeler," one says, "We don't have time to build up to love scenes." Opening up the mechanics of movie making for laughs was a Keaton trick he would revisit time and again, culminating with Sherlock Jr. in 1924 when a projectionist gets sucked into the film itself.

The next two shorts, Good Night, Nurse and The Cook, both came out after Keaton had shipped out for the European war and his contributions look hasty, as if he filmed a couple of scenes for both, leaving the main plot for Arbuckle to flesh out later. Still, they're both worth a look, particularly The Cook which was thought to be lost for decades until rediscovered in Norway in 1999.

After a year in the Army left Keaton deaf in one ear, he went right back to making short films with Arbuckle. The first of them, Back Stage, is a traditional "hey kids, lets put on a play" story with one extraordinary scene—anticipating Keaton's most famous stunt in 1928's Steamboat Bill Jr., a house falls on Arbuckle only to miss him thanks to an open second floor window. Here, the house is only a cardboard stage prop and, unlike that latter example which might have killed Keaton, nobody is in danger, but seeing this early attempt at a famous gag is a bit like finding a preliminary sketch of Picasso's Guernica on the back of a cocktail napkin.

There were two more shorts, The Hayseed in 1919 and The Garage in 1920, after which Arbuckle left to make full-length feature films, but not before leaving the keys to the studio to Keaton. With Arbuckle's public blessing, Keaton began to direct films of his own.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Of all the developments that made 1917 such a landmark year in film—the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist—perhaps the happiest for movie fans today was the big screen debut of the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

That Buster Keaton is only now arriving on the scene may come as a bit of a surprise to those of us who naturally think of Keaton as a contemporary of Chaplin—certainly we frame the debate "Chaplin versus Keaton" in those terms—but the fact is, Chaplin was already an international star with sixty films to his credit (including forty he directed himself) before Keaton ever set foot in a film studio. And although Keaton would brilliantly subvert most of the rules of early film comedy in a brief but prolific run between 1920 and 1928, it was by and large Chaplin who had established those rules, a fact that Keaton himself later conceded.

Which is not to say Keaton was an amateur when he joined Roscoe Arbuckle during the filming of The Butcher Boy in early 1917. He had been performing on the vaudeville stage with his parents from the age of four as part of a rough and tumble "knockabout" comedy act.

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."

Legend has it he was dubbed "Buster" when escape artist Harry Houdini saw the infant Keaton take a fall down a flight of stairs and bounce up unharmed. Whether he was born with it, or developed it doing routines with his father, if Keaton wasn't the most talented pratfall artist in movie history, I'd like to see the guy who survived long enough to be a better one. He did stunts that rivaled those of Douglas Fairbanks, and when he was done, he doubled for his co-stars and did their stunts, too.

"The secret," he once said, "is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat."

In early 1917, Keaton was booked into New York's Winter Garden for a series of shows when he bumped into Roscoe Arbuckle while strolling down Broadway.

For those of you who only know Arbuckle—"Fatty" to his fans, "Roscoe" to his friends—through the tabloid scandal and subsequent trial that (despite his acquittal) ended his career, you're missing out on one of the greatest comedic actor-directors of the silent era. Although I wouldn't put him in the same league as "the three geniuses"—Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd—Arbuckle was, in terms of his popularity and impact, the best of the rest, the very top of the second tier of comedians that included Mabel Normand, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, Ford Sterling and Max Linder.

Mark Bourne in his review of the Arbuckle/Keaton collection for The DVD Journal suggested that Arbuckle was to his biggest commercial rival, Charlie Chaplin, what Adam Sandler is these days to Woody Allen, "less artistic and sophisticated by miles, but nonetheless obviously skilled and unquestionably popular with his own characteristic wacky and raucous manner."

The collaboration between Keaton and Arbuckle was to prove pivotal for Buster.

"Arbuckle asked me if I'd ever been in a motion picture," Keaton told Kevin Brownlow in 1964. "I said I hadn't even been in a studio. He said, 'Come on down to the Norma Talmadge Studio on Forty-eighth Street on Monday. Get there early and do a scene with me and see how you like it.' Well, rehearsals [at the Winter Garden] hadn't started yet, so I said, 'all right.' I went down and we did it."

That first scene, in the Arbuckle short comedy The Butcher Boy, ends in one of the best of Keaton's early gags. At the 6:25 mark of the film, Keaton wanders into the country store where Arbuckle works as a butcher and by the end of the scene, Keaton's trademark porkpie hat is full of molasses and the store is a wreck.

"The first time I ever walked in front of a motion picture camera," he said, "that scene is in the finished motion picture and instead of doing just a bit [Arbuckle] carried me all the way through it."

It's a terrific sequence, but it's as notable for what isn't in it as what is—Keaton does not wear an outrageous costume or wild facial hair, nor does he indulge in the over-the-top reactions and shameless mugging common to the era. He's just a thoroughly average American—albeit, one who can take a swipe at Al St. John, do a 360º spin in mid-air and wind up flat on his back—who has somehow wandered in off the street and found himself thrust into the insanity of a two-reel silent comedy.

Keaton's understatement was the antithesis of the Mack Sennett approach, and was so wholly original, it constituted something of a revolution. Audiences and critics alike instantly took note, if not always approvingly.

"The deadpan was a natural," Keaton said. "As I grew up on the stage, experience taught me that I was the type of comedian that if I laughed at what I did, the audience didn't. Well, by the time I went into pictures when I was twenty-one, working with a straight face, a sober face, was mechanical with me.

"I got the reputation immediately [of being] called 'frozen face,' 'blank pan' and things like that. We went into the projection room and ran our first two pictures to see if I'd smiled. I hadn't paid any attention to it. We found out I hadn't. It was just a natural way of acting."

But deadpan, as any Keaton fan can tell you, isn't synonymous with inert, and as film historian Gilberto Perez has noted, Keaton was able to show us a face, "by subtle inflections, so vividly expressive of inner life. His large deep eyes are the most eloquent feature; with merely a stare he can convey a wide range of emotions, from longing to mistrust, from puzzlement to sorrow."

Keaton's next film with Arbuckle, The Rough House, is one of their best. Not only does it feature some of the best gags of Arbuckle's career—the dancing dinner rolls, trying to douse a raging fire with a teacup, squeezing out a bowl of soup with a sponge—but many film historians also now list Keaton as its uncredited co-director.

"The first thing I did in the studio," he told Robert and Joan Franklin in 1958, "was to tear that camera to pieces. I had to know how that film got into the cutting-room, what you did to it in there, how you projected it, how you finally got the picture together, and how you made things match. The technical part of pictures is what interested me."

Keaton and Arbuckle made three more comedies in 1917, His Wedding Night, Oh Doctor! and Coney Island. Each features an aspect of Keaton rarely seen after.

In the first, Keaton plays a milliner's delivery boy and winds up in drag as he models a wedding dress. Mistaking him for the bride, Al St. John kidnaps Keaton and hauls him off to the preacher at gunpoint.

In Oh, Doctor!, he plays Arbuckle's little boy, a reprise of the sort of comedy Keaton and his father Joe had done for years on stage, and pulls off a stunt you have to see to believe—Arbuckle smacks him, Keaton tumbles backwards over a table, picks up a book as he falls, and lands upright in a chair, with the book on his lap as if he's been there all along, reading comfortably.

And while Coney Island is mostly an excuse to watch Arbuckle caper around Luna Park—its plot of men wooing women on park benches is a throwback to the Keystone comedies—the film is worth seeking out for two reasons: one, for its documentary footage of Coney Island nearly one hundred years ago, and two, a rare chance to see Buster Keaton smile!

The smile notwithstanding, in terms of his look, his acting style, his fearless physical stunts and his fascination with technology, the basic Keaton was already on full display in these early two-reel comedies. He had only to add the context—that of a rational man enmeshed in the machinery of a universe that exists only to achieve absurd ends—for his unique brand of humor to reach its full flower.

In 1918, Keaton made five more two-reel comedies with Arbuckle before shipping off to France to serve in the army during World War I. Although not credited as such, by this time Keaton was working as the assistant director when Arbuckle, the credited director, was in front of the camera.

"You fell into those jobs," Keaton said later. "He never referred to me as the assistant director, but I was the guy who sat alongside of the camera and watched scenes that he was in. I ended up just practically co-directing with him."

The new balance in their collaboration showed up in front of the camera as well. In the first three films of 1918, he and Arbuckle are equal partners, more Laurel and Hardy—with Keaton as a thin straight man and Arbuckle a rotund goof—than the star/supporting player dynamic of 1917. The first film of the year, Out West is a parody of the Western genre, popular at the time, with Arbuckle playing a drifter riding the rails who winds up working for Keaton as an uncharacteristically tough saloon owner. Parody would soon prove to be one of Keaton's trademarks—indeed, his two-reeler The Frozen North in 1922 was such a savage parody of William S. Hart's "good bad guy" westerns that Hart refused to speak to Keaton for two years.

Next up was The Bell Boy, the story of two Stooge-like bellhops in a shabby hotel. The horse-drawn elevator is pure Keaton who was always fascinated by machines, and built several movies around them, culminating in his classic train picture, The General.

The film that followed, Moonshine, is the most Keatonesque of all his collaborations with Arbuckle. Ostensibly the story of a pair of inept revenuers (Keaton and Arbuckle) hot on the trail of West Virginia bootleggers, this is really a movie about movies, with the title cards constantly breaking the fourth wall to explain the filming process. "Look, this is only a two-reeler," one says, "We don't have time to build up to love scenes." Opening up the mechanics of movie making for laughs was a Keaton trick he would revisit time and again, culminating with Sherlock Jr. in 1924 when a projectionist gets sucked into the film itself.

The next two shorts, Good Night, Nurse and The Cook, both came out after Keaton had shipped out for the European war and his contributions look hasty, as if he filmed a couple of scenes for both, leaving the main plot for Arbuckle to flesh out later. Still, they're both worth a look, particularly The Cook which was thought to be lost for decades until rediscovered in Norway in 1999.

After a year in the Army left Keaton deaf in one ear, he went right back to making short films with Arbuckle. The first of them, Back Stage, is a traditional "hey kids, lets put on a play" story with one extraordinary scene—anticipating Keaton's most famous stunt in 1928's Steamboat Bill Jr., a house falls on Arbuckle only to miss him thanks to an open second floor window. Here, the house is only a cardboard stage prop and, unlike that latter example which might have killed Keaton, nobody is in danger, but seeing this early attempt at a famous gag is a bit like finding a preliminary sketch of Picasso's Guernica on the back of a cocktail napkin.

There were two more shorts, The Hayseed in 1919 and The Garage in 1920, after which Arbuckle left to make full-length feature films, but not before leaving the keys to the studio to Keaton. With Arbuckle's public blessing, Keaton began to direct films of his own.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Chaplin At 124

In honor of his birthday today, here's a portion of my most popular post about Charlie Chaplin.

"I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time."—Buster Keaton, in a 1960 interview with Herbert Feinstein

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After Chaplin's contract at Essanay expired, he signed with the Mutual Film Corporation to direct and star in a dozen two-reel comedies—known colloquially as "the Chaplin Mutuals"—for the then-unheard of sum of $670,000, the most any entertainer had been paid in history. "Next to the war in Europe," a Mutual publicist wrote, "Chaplin is the most expensive item in contemporaneous history." The deal with Mutual afforded Chaplin two luxuries he'd never had before as a director—time and money—and he took full advantage of the opportunity, not only re-shooting sequences that didn't match his vision, but also experimenting with the comedic form itself.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

As his leading lady, Chaplin brought Edna Purviance with him from Essanay. Purviance (Purr-VYE-ance) had been working as a stenographer in San Francisco when she caught Chaplin's eye, who, either as a trite come-on or because he could more easily mold the novice actress to fit his ideas of comedy, asked her if she would like to be in pictures. "I laughed at the idea," she said later, "but agreed to try it."

Although their romantic relationship was brief, Purviance continued to play Chaplin's leading lady for nine years, appearing in approximately forty films (the exact number is in dispute), more than any other actress.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Each film is a loose collection of well-polished comic set-ups and payoffs, distinguishable from Chaplin's work at Keystone and Essanay only be the quality of their gags.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

Chaplin returned to form with his next film, One A.M., which combined elements from a pair of Max Linder "drunk comedies," First Cigar and Max Takes Tonics, to create a one-man tour de force that plays a little like a wager that a single joke—a drunk fumbling his way up a flight of stairs to bed—can work for twenty uninterrupted minutes.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

As in most of his films, the camera work is spare, the editing unobtrusive, with both focused on featuring the best available performance rather than solving technical problems such as continuity or matching edits. Like Fred Astaire, who insisted his dances be filmed in an uninterrupted take with an angle wide and long enough to show the performance from head to toe, Chaplin mostly used long shots and uninterrupted takes to show his audience that the dance-like rhythm of his intricate physical gags are not cheats conjured up in the editing room, but reflect his real abilities. Anyway, I'm no fan of fancy camera work that exists only to prove the director wasn't napping during that day's lecture at film school and though Chaplin's style remained primitive compared to his contemporaries, it was a conscious choice with a specific payoff in mind.

Chaplin finished out 1916 with four films—The Count, The Pawnshop, Behind The Screen and The Rink—that returned to familiar formulas, but the comedy was well thought out, as funny as anything he had ever done. Of the four, I'd rate The Pawnshop and especially Behind The Screen the most highly. In the former watch particularly for the Tramp's efforts to evaluate the alarm clock Albert Austin has brought into the shop to pawn—do I need to tell you how things work out for Austin and the clock?

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

Chaplin opened 1917 with one of the most beloved comedies of his career, Easy Street. Set in the slums of New York, the Tramp wanders into a Salvation Army style mission and falls instantly in love with the pianist (Edna Purviance, of course). Determined to redeem himself in her eyes, the Tramp volunteers for a job as a policeman with a beat on the notorious Easy Street (which is anything but). The Tramp's battles with the local bully—Campbell, who is a foot taller and a foot wider than Chaplin—provides the bulk of the comedy.

Easy Street is particularly harsh, populated with drug addicts, rapists, wife beaters, and hungry children, the sort of neighborhood Chaplin himself grew up in as the son of an alcoholic father and mentally-ill mother, yet the finished film is pure laughs and I never feel like Chaplin is lecturing or hectoring us.

He would return to this setting in 1921 for his first feature-length film, The Kid.

Typical of the Mutual era, Chaplin followed the personal with the formulaic, this time with The Cure, another drunk act reminiscent of One A.M. except this time with a sanitarium full of rich hypochondriacs instead of furniture to trip over. Again, Chaplin takes simple jokes, such as a man caught in a revolving door, and stretches them to unbelievable lengths, repeating them, adding new elements, changing payoffs. In one scene, Chaplin—here playing a rich alcoholic rather than the Tramp—attempts to drink from the health-giving spring that is the facility's main attraction, yet always winds up filling up his hat instead. Later, though, after the stash of booze he's smuggled in to tide him over during rehab winds up in the well, he of course doesn't spill a drop.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

Chaplin's next film, The Immigrant, his eleventh at Mutual, is not the funniest, but I would argue it was the most important—maybe the single most important development in movie comedy from any source to that time.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

In a short chock full of comedy, Chaplin managed to show the hardship's immigrants faced as they tried to reach America—intolerable shipboard conditions including overcrowding, theft, execrable food, illness; the humiliation of being herded like cattle through Ellis Island; and finally, after landing in New York, the linguistic, economic and cultural hurdles, as well as nativist hostility, involved in adapting to every day life in a foreign country, demonstrated in this case through an act as simple as ordering dinner in a restaurant.

Yet Chaplin also captures the hope and promise that America at that time represented to millions worldwide. The scene of hopeful passengers crowding the deck to watch in silence as the ship sails past the Statue of Liberty is justly one of the most famous of the silent era. And the giddiness with which the Tramp courts the Girl (Purviance) is a perfect expression of the indomitable human will to survive.

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

If he wasn't already, Chaplin's Tramp was from this point forward identified with those first-generation immigrants then making up more than ten percent of America's population, as well as with those abroad who yearned to breathe free.

"The Immigrant," Chaplin said years later, "touched me more than any other film I made."

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

The Immigrant is preserved in the National Film Registry.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

After Mutual, Chaplin scored his first million dollar payday, signing with First National, a association of independent theater owners seeking a cut of the lucrative film distribution pie. Under the terms of the contract, Chaplin was to direct eight two-reel comedies, but the twenty minute format could not longer satisfy his artistic ambitions. Before his deal with First National was done, Chaplin had directed, among other things, his first feature length film, The Kid, as well as the four-reel war comedy, Shoulder Arms.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

Despite reaching ever more dizzying heights of fame, fortune and artistic achievement, Chaplin later confessed his years at Mutual were the happiest of his life. "I was light and unencumbered," he wrote, "twenty-seven years old, with fabulous prospects and a friendly, glamorous world before me."

Years later, Chaplin's son Sydney found himself at the Silent Movie Theater in Hollywood enjoying a revival of Chaplin's Mutuals only to be out-laughed by an elderly gentleman a few rows behind him. Turning to investigate he discovered "[i]t was my father who was laughing the loudest! Tears were rolling down his cheeks from laughing so hard and he had to wipe his eyes with his handkerchief."

"Perhaps," wrote Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance, "[Chaplin] had great fondness for the Mutuals simply for the same reason that generations of audiences have as well—because of the sheer joy, comic inventiveness, and hilarity of this extraordinary series of films."

"I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time."—Buster Keaton, in a 1960 interview with Herbert Feinstein

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.After Chaplin's contract at Essanay expired, he signed with the Mutual Film Corporation to direct and star in a dozen two-reel comedies—known colloquially as "the Chaplin Mutuals"—for the then-unheard of sum of $670,000, the most any entertainer had been paid in history. "Next to the war in Europe," a Mutual publicist wrote, "Chaplin is the most expensive item in contemporaneous history." The deal with Mutual afforded Chaplin two luxuries he'd never had before as a director—time and money—and he took full advantage of the opportunity, not only re-shooting sequences that didn't match his vision, but also experimenting with the comedic form itself.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals. And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics. As his leading lady, Chaplin brought Edna Purviance with him from Essanay. Purviance (Purr-VYE-ance) had been working as a stenographer in San Francisco when she caught Chaplin's eye, who, either as a trite come-on or because he could more easily mold the novice actress to fit his ideas of comedy, asked her if she would like to be in pictures. "I laughed at the idea," she said later, "but agreed to try it."

Although their romantic relationship was brief, Purviance continued to play Chaplin's leading lady for nine years, appearing in approximately forty films (the exact number is in dispute), more than any other actress.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.Each film is a loose collection of well-polished comic set-ups and payoffs, distinguishable from Chaplin's work at Keystone and Essanay only be the quality of their gags.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love. The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.Chaplin returned to form with his next film, One A.M., which combined elements from a pair of Max Linder "drunk comedies," First Cigar and Max Takes Tonics, to create a one-man tour de force that plays a little like a wager that a single joke—a drunk fumbling his way up a flight of stairs to bed—can work for twenty uninterrupted minutes.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.As in most of his films, the camera work is spare, the editing unobtrusive, with both focused on featuring the best available performance rather than solving technical problems such as continuity or matching edits. Like Fred Astaire, who insisted his dances be filmed in an uninterrupted take with an angle wide and long enough to show the performance from head to toe, Chaplin mostly used long shots and uninterrupted takes to show his audience that the dance-like rhythm of his intricate physical gags are not cheats conjured up in the editing room, but reflect his real abilities. Anyway, I'm no fan of fancy camera work that exists only to prove the director wasn't napping during that day's lecture at film school and though Chaplin's style remained primitive compared to his contemporaries, it was a conscious choice with a specific payoff in mind.

Chaplin finished out 1916 with four films—The Count, The Pawnshop, Behind The Screen and The Rink—that returned to familiar formulas, but the comedy was well thought out, as funny as anything he had ever done. Of the four, I'd rate The Pawnshop and especially Behind The Screen the most highly. In the former watch particularly for the Tramp's efforts to evaluate the alarm clock Albert Austin has brought into the shop to pawn—do I need to tell you how things work out for Austin and the clock?

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.Chaplin opened 1917 with one of the most beloved comedies of his career, Easy Street. Set in the slums of New York, the Tramp wanders into a Salvation Army style mission and falls instantly in love with the pianist (Edna Purviance, of course). Determined to redeem himself in her eyes, the Tramp volunteers for a job as a policeman with a beat on the notorious Easy Street (which is anything but). The Tramp's battles with the local bully—Campbell, who is a foot taller and a foot wider than Chaplin—provides the bulk of the comedy.

He would return to this setting in 1921 for his first feature-length film, The Kid.

Typical of the Mutual era, Chaplin followed the personal with the formulaic, this time with The Cure, another drunk act reminiscent of One A.M. except this time with a sanitarium full of rich hypochondriacs instead of furniture to trip over. Again, Chaplin takes simple jokes, such as a man caught in a revolving door, and stretches them to unbelievable lengths, repeating them, adding new elements, changing payoffs. In one scene, Chaplin—here playing a rich alcoholic rather than the Tramp—attempts to drink from the health-giving spring that is the facility's main attraction, yet always winds up filling up his hat instead. Later, though, after the stash of booze he's smuggled in to tide him over during rehab winds up in the well, he of course doesn't spill a drop.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.Chaplin's next film, The Immigrant, his eleventh at Mutual, is not the funniest, but I would argue it was the most important—maybe the single most important development in movie comedy from any source to that time.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.In a short chock full of comedy, Chaplin managed to show the hardship's immigrants faced as they tried to reach America—intolerable shipboard conditions including overcrowding, theft, execrable food, illness; the humiliation of being herded like cattle through Ellis Island; and finally, after landing in New York, the linguistic, economic and cultural hurdles, as well as nativist hostility, involved in adapting to every day life in a foreign country, demonstrated in this case through an act as simple as ordering dinner in a restaurant.

Yet Chaplin also captures the hope and promise that America at that time represented to millions worldwide. The scene of hopeful passengers crowding the deck to watch in silence as the ship sails past the Statue of Liberty is justly one of the most famous of the silent era. And the giddiness with which the Tramp courts the Girl (Purviance) is a perfect expression of the indomitable human will to survive.

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."If he wasn't already, Chaplin's Tramp was from this point forward identified with those first-generation immigrants then making up more than ten percent of America's population, as well as with those abroad who yearned to breathe free.

"The Immigrant," Chaplin said years later, "touched me more than any other film I made."

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.The Immigrant is preserved in the National Film Registry.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.After Mutual, Chaplin scored his first million dollar payday, signing with First National, a association of independent theater owners seeking a cut of the lucrative film distribution pie. Under the terms of the contract, Chaplin was to direct eight two-reel comedies, but the twenty minute format could not longer satisfy his artistic ambitions. Before his deal with First National was done, Chaplin had directed, among other things, his first feature length film, The Kid, as well as the four-reel war comedy, Shoulder Arms.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.Despite reaching ever more dizzying heights of fame, fortune and artistic achievement, Chaplin later confessed his years at Mutual were the happiest of his life. "I was light and unencumbered," he wrote, "twenty-seven years old, with fabulous prospects and a friendly, glamorous world before me."

Years later, Chaplin's son Sydney found himself at the Silent Movie Theater in Hollywood enjoying a revival of Chaplin's Mutuals only to be out-laughed by an elderly gentleman a few rows behind him. Turning to investigate he discovered "[i]t was my father who was laughing the loudest! Tears were rolling down his cheeks from laughing so hard and he had to wipe his eyes with his handkerchief."

"Perhaps," wrote Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance, "[Chaplin] had great fondness for the Mutuals simply for the same reason that generations of audiences have as well—because of the sheer joy, comic inventiveness, and hilarity of this extraordinary series of films."

Monday, April 8, 2013

Mary Pickford: A Five-Film Primer

Today is Mary Pickford's birthday. One of the greatest stars of the silent era, and pound-for-pound the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Mary Pickford's work is indispensable for the film fanatic. If you've never seen a Mary Pickford movie and don't know where to begin, here are five films to get you started.

The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917)

An unprecedented blend of comedy and melodrama that worried the studio but delighted its star, the story of a girl whose wealthy parents neglect her while others prey on her could easily have become sentimental claptrap. Instead, Pickford's Gwendolyn is, by turns, impetuous, flighty and sullen, but also curious, kind and fun—in other words, a real girl. The film was one of the biggest hits of 1917 and is a National Film Registry selection.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917)

A cross between Charles Dickens and Louisa May Alcott, this story of a poor girl sent to live with a pair of maiden aunts is the most typical example of a Mary Pickford movie. Boasting plenty of comedy with a soupçon of pathos in the final act, Rebecca was Pickford's biggest hit yet.

Stella Maris (1918)

Based on a novel by William J. Locke, Stella Maris is a Victorian melodrama of the first water, the riveting story of two girls, one a rich shut-in sheltered from life's realities, the other, an ugly duckling orphan—both played by Pickford—whose paths intersect with tragic results. Variety called the performance "a revelation," the Los Angeles Times deemed it "brilliant, powerful and poignant" and studio chief Adolph Zukor later called it "the most remarkable thing which Mary Pickford has ever done for the screen." And they were right.

Sparrows (1926)

The other contender for Pickford's best movie, Sparrows is the harrowing tale of a group of backwoods orphans menaced by white slavers. In a sort of teenage take on Lillian Gish's gun-toting granny in 1955's The Night of the Hunter, Pickford attempts to lead her wards to safety while danger lurks at every turn—including the very real alligators director William Beaudine brought onto the set.

My Best Girl (1927)

In a rare adult role, Pickford plays a shop girl who falls in love with the owner's son. Played strictly for laughs, the result is a nifty little comedy, as fresh and light and funny as the actress who carries it on her back. As film critic Steve Vineberg says, the performance is "an extraordinary combination of spunk and delicacy." And as an added bonus, look for a brief, pre-stardom appearance by Carole Lombard as one of the shop girls.

The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917)

An unprecedented blend of comedy and melodrama that worried the studio but delighted its star, the story of a girl whose wealthy parents neglect her while others prey on her could easily have become sentimental claptrap. Instead, Pickford's Gwendolyn is, by turns, impetuous, flighty and sullen, but also curious, kind and fun—in other words, a real girl. The film was one of the biggest hits of 1917 and is a National Film Registry selection.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917)

A cross between Charles Dickens and Louisa May Alcott, this story of a poor girl sent to live with a pair of maiden aunts is the most typical example of a Mary Pickford movie. Boasting plenty of comedy with a soupçon of pathos in the final act, Rebecca was Pickford's biggest hit yet.

Stella Maris (1918)

Based on a novel by William J. Locke, Stella Maris is a Victorian melodrama of the first water, the riveting story of two girls, one a rich shut-in sheltered from life's realities, the other, an ugly duckling orphan—both played by Pickford—whose paths intersect with tragic results. Variety called the performance "a revelation," the Los Angeles Times deemed it "brilliant, powerful and poignant" and studio chief Adolph Zukor later called it "the most remarkable thing which Mary Pickford has ever done for the screen." And they were right.

Sparrows (1926)

The other contender for Pickford's best movie, Sparrows is the harrowing tale of a group of backwoods orphans menaced by white slavers. In a sort of teenage take on Lillian Gish's gun-toting granny in 1955's The Night of the Hunter, Pickford attempts to lead her wards to safety while danger lurks at every turn—including the very real alligators director William Beaudine brought onto the set.

My Best Girl (1927)

In a rare adult role, Pickford plays a shop girl who falls in love with the owner's son. Played strictly for laughs, the result is a nifty little comedy, as fresh and light and funny as the actress who carries it on her back. As film critic Steve Vineberg says, the performance is "an extraordinary combination of spunk and delicacy." And as an added bonus, look for a brief, pre-stardom appearance by Carole Lombard as one of the shop girls.

Sunday, April 29, 2012

The Silent Oscars: 1917

We speak of 1939 as being the greatest year in Hollywood history—and who am I to disagree—but you would be remiss not to count 1917 in the mix. That was the year of the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist, and the big screen debut of arguably the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

We speak of 1939 as being the greatest year in Hollywood history—and who am I to disagree—but you would be remiss not to count 1917 in the mix. That was the year of the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist, and the big screen debut of arguably the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.Beat that!

PICTURE

winner: The Chaplin Mutuals (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer) (prod. Charles Chaplin)

nominees: The Poor Little Rich Girl (prod. Adolph Zukor); Rebecca Of Sunnybrook Farm (prod. Mary Pickford); Terje Vigen a.k.a. A Man There Was (prod. Charles Magnusson); Umirayushchii Lebed a.k.a. The Dying Swan (prod. Aleksandr Khanzhonkov)

Must-See Movies: The Adventurer; The Cure; Easy Street; The Immigrant; The Poor Little Rich Girl

Recommended Films: The Butcher Boy; Coney Island; Down To Earth; Oh Doctor!; Reaching For The Moon; Rebecca Of Sunnybrook Farm; A Romance Of The Redwoods; The Rough House; Terje Vigen a.k.a. A Man There Was; Umirayushchii Lebed a.k.a. The Dying Swan; Wild and Woolly

Of Interest: Das Fidele Gefängnis a.k.a. The Merry Jail; Furcht; The Heart Of Texas Ryan a.k.a. Single Shot Parker; His Wedding Night; A Modern Musketeer; Over The Fence; Straight Shooting; Teddy At The Throttle

ACTOR

winner: Charles Chaplin (The Chaplin Mutuals) (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer)

nominees: Roscoe Arbuckle (The Roscoe Arbuckle Comedy Shorts); Harry Carey (Straight Shooting and Bucking Broadway); Elliott Dexter (A Romance Of The Redwoods); Douglas Fairbanks (Wild and Woolly, Down To Earth and Reaching For The Moon); William Farnum (A Tale Of Two Cities)

ACTRESS

winner: Mary Pickford (The Poor Little Rich Girl and Rebecca Of Sunnybrook Farm)

nominees: Vera Karalli (Umirayushchii Lebed a.k.a. The Dying Swan); Doris Kenyon (A Girl's Folly); Ossi Oswalda (Das Fidele Gefängnis a.k.a. The Merry Jail)

DIRECTOR

winner: Charles Chaplin (The Chaplin Mutuals) (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer)

nominees: Yevgeni Bauer (Umirayushchii Lebed a.k.a. The Dying Swan); Victor Sjöström (Terje Vigen a.k.a. A Man There Was); Maurice Tourneur (The Poor Little Rich Girl)

SUPPORTING ACTOR

winner: Buster Keaton (The Roscoe Arbuckle Comedy Shorts)

nominees: Eric Campbell (The Chaplin Mutuals) (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer); Sam De Grasse (Wild And Woolly)

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

winner: Edna Purviance (The Chaplin Mutuals) (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer)

nominees: Bebe Daniels (The Harold Lloyd Comedy Shorts); June Elvidge (A Girl's Folly); ZaSu Pitts (A Little Princess); Florence Vidor (A Tale Of Two Cities)

SCREENPLAY

winner: Frances Marion, from a play by Eleanor Gates (The Poor Little Rich Girl)

nominees: Charles Chaplin (The Chaplin Mutuals) (Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer); Anita Loos and John Emerson, story by Horace B. Carpenter (Wild and Woolly); Frances Marion, from a play by Charlotte Thompson and a novel by Kate Douglas Wiggin (Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm)

SPECIAL AWARDS

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Variations On A Gag #1—The Comedian As Sanitarium Patient

Stealing is a time honored tradition among comedians, and God bless them, I say—thanks to their thieving ways, we can directly compare comedy acts with different styles and of different eras and get a sense of what each brings to the table.

Stealing is a time honored tradition among comedians, and God bless them, I say—thanks to their thieving ways, we can directly compare comedy acts with different styles and of different eras and get a sense of what each brings to the table.This is especially true, I think, where as here, the players are not at the top of their games. Great work tends to transcend its source material, and even if it's still identifiably the work of its creator, largely becomes something unique. Merely good work, on the other hand, especially when done in a hurry for money, tends to reveal its creator's default tendencies.

In this case, Charlie Chaplin, Roscoe Arbuckle and the Three Stooges all check themselves in as patients in a sanitarium and in each case, you can see them race for the tried and true. Chaplin leans on repetition and rhythm, Arbuckle on pratfalls and cross-dressing, the Stooges on destructive ineptitude. All did better work, but none more typical.

Charles Chaplin in The Cure (1917).

Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton in Good Night, Nurse (1918).

The Three Stooges in Monkey Businessmen (1946) (in two parts).

Saturday, October 22, 2011

The Silent Oscars: 1917—Part Four

To see my awards for 1917, click here. To read about Mary Pickford, click here. And to read about the Chaplin Mutuals, click here.

The Short Comedies of Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton

The Short Comedies of Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton

Of all the developments that made 1917 such a landmark year in film—the industry-wide adoption of what is now known as "classical continuity editing," Mary Pickford's emergence as the most powerful woman in Hollywood history, Charlie Chaplin's maturation as an artist—perhaps the happiest for movie fans today was the big screen debut of arguably the greatest film comedian of all time, Buster Keaton.

That Buster Keaton is only now arriving on the scene may come as a bit of a surprise to those of us who naturally think of Keaton as a contemporary of Chaplin—certainly we frame the debate "Chaplin versus Keaton" in those terms—but the fact is, Chaplin was already an international star with sixty films to his credit (including forty he directed himself) before Keaton ever set foot in a film studio. And although Keaton would brilliantly subvert most of the rules of early film comedy in a brief but prolific run between 1920 and 1928, it was by and large Chaplin who had established those rules, a fact that Keaton himself later conceded.

Or to put it another way, Keaton was to Chaplin what the Beatles were to Elvis, building a cathedral on the foundation the other had laid.

Or to put it another way, Keaton was to Chaplin what the Beatles were to Elvis, building a cathedral on the foundation the other had laid.

Which is not to say Keaton was an amateur when he joined Roscoe Arbuckle during the filming of The Butcher Boy in early 1917. He had been performing on the vaudeville stage with his parents from the age of four as part of a rough and tumble "knockabout" comedy act.

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."

"I'd just simply get in my father's way all the time," Keaton said, "and get kicked all over the stage. But we always managed to get around the [child labor] law," he added, "because the law read: No child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze—and it named everything—but none of them said you couldn't kick him in the face."